Resonance structures are a fundamental concept in organic chemistry, helping explain the stability, bonding, and reactivity of many molecules. When a molecule cannot be accurately described by a single Lewis structure, chemists use resonance to represent its true electronic distribution. These structures are essential for understanding aromaticity, delocalization, and charge distribution in compounds like benzene, carboxylates, and conjugated systems. In this article, we’ll explore what resonance structures are, how to draw them, and why they matter in predicting molecular behavior.

What Are Resonance Structures?

Curious about resonance structures? Eureka Technical Q&A explains how they represent electron delocalization in molecules, helping you understand molecular stability, bonding, and chemical behavior.

Resonance structures are two or more valid Lewis structures that represent the same molecule but differ in the arrangement of electrons, particularly π electrons and lone pairs. They do not represent different molecules, but rather different ways of illustrating the same molecule’s electron distribution.

The real structure is a resonance hybrid—a weighted average of all possible resonance forms—reflecting the delocalization of electrons across multiple atoms. This delocalization contributes to molecular stability.

When Do Molecules Have Resonance?

A molecule exhibits resonance when:

- It contains delocalized π electrons across adjacent atoms or bonds

- There are multiple ways to place double bonds and lone pairs without changing atom positions

- The involved atoms maintain full valence shells in each form

Common features include:

- Conjugated systems with alternating single and double bonds

- Lone pairs adjacent to π bonds or empty p-orbitals

- Charged structures that can spread the charge over multiple atoms

How to Draw Resonance Structures

- Keep atom positions the same

Only move electrons—not atoms. The skeleton of the molecule remains unchanged. - Use curved arrows

Use formal curved-arrow notation to show the movement of electrons (from a lone pair or a π bond to a new position). - Check octet rule

Ensure all atoms follow the octet rule unless dealing with exceptions like boron or expanded octets (in sulfur, phosphorus, etc.). - Distribute charges properly

Assign formal charges where necessary, and ensure total charge remains consistent across all forms. - Evaluate stability

More stable resonance forms contribute more to the hybrid. Stability increases when:- Charges are minimized

- Negative charges are on more electronegative atoms

- Octets are satisfied

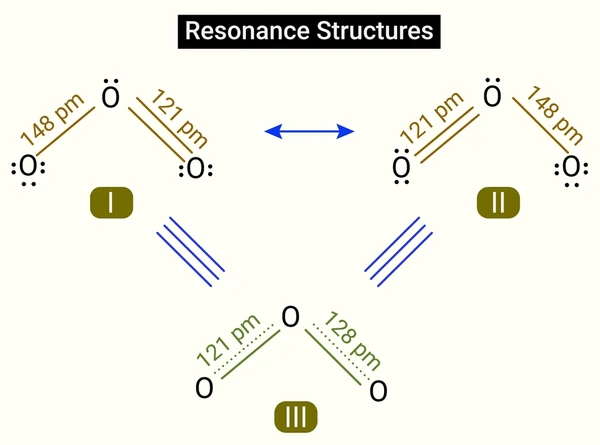

Example: Resonance in the Carboxylate Ion

Take the carboxylate ion (R–COO⁻) as an example. It has two resonance structures:

- One with a double bond between the carbon and one oxygen, and a negative charge on the other oxygen

- Another with the double bond and negative charge positions switched

The true structure is a hybrid where the negative charge is delocalized over both oxygen atoms, making both C–O bonds equivalent in length and strength. This delocalization explains why carboxylate ions are more stable than their non-resonant counterparts.

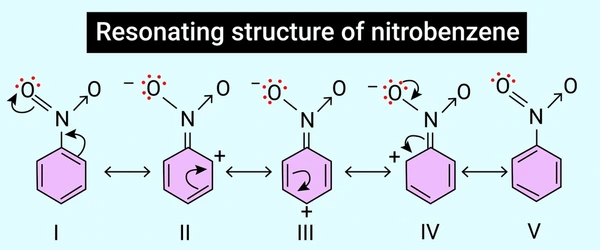

Resonance in Benzene and Aromatic Compounds

Benzene (C₆H₆) is a textbook example of resonance. It can be drawn with alternating single and double bonds around a six-carbon ring, but in reality, all bonds are equivalent.

This equal bond length and the stability of benzene arise from resonance delocalization of π electrons over the ring. The resonance hybrid provides a more accurate representation of its aromaticity and explains why benzene is less reactive than typical alkenes.

Why Resonance Matters

- Explains Stability: Delocalization lowers energy, making molecules more stable

- Predicts Reactivity: Helps understand electrophilic and nucleophilic attack points

- Determines Structure: Clarifies bond lengths, angles, and geometry

- Supports Acid-Base Behavior: Stabilized conjugate bases through resonance make stronger acids

- Guides Reaction Mechanisms: Curved-arrow electron flow depends on resonance possibilities

Understanding resonance helps chemists predict how molecules behave, especially in complex organic reactions.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Moving atoms instead of electrons

- Breaking the octet rule inappropriately

- Ignoring formal charges

- Drawing resonance between structures that aren’t valid (e.g., breaking sigma bonds)

Remember, resonance structures are not real by themselves—they’re tools to understand the real hybrid.

FAQs About Resonance Structures

Is resonance the same as tautomerism?

No. Resonance involves delocalized electrons without atom movement. Tautomerism involves a real shift in atom positions (usually hydrogen), creating distinct compounds in equilibrium.

Can resonance occur in non-organic molecules?

Yes. Many inorganic ions (e.g., nitrate, sulfate) also exhibit resonance.

How do I know which resonance structure is most important?

The most stable ones have complete octets, minimal charge separation, and place charges on atoms best suited to carry them.

Do resonance structures affect bond length?

Yes. Bonds involved in resonance tend to have intermediate lengths, between a single and double bond.

Why does resonance increase acidity?

If the conjugate base is stabilized by resonance, the original acid more readily donates its proton, increasing acidity.

Conclusion

Resonance structures are vital for accurately understanding molecular behavior in organic chemistry. They offer insight into bond stability, molecular shape, and reactivity. By learning how to draw and evaluate resonance forms, chemists gain a deeper understanding of reaction mechanisms and structural predictions.

Whether you’re analyzing the stability of a molecule or mapping out a reaction pathway, mastering resonance is a key step in becoming fluent in the language of chemistry.

To get detailed scientific explanations of Resonance Structures, try Patsnap Eureka.