Comparison of Neuromorphic and Traditional Computing Material Efficiency

OCT 27, 202510 MIN READ

Generate Your Research Report Instantly with AI Agent

Patsnap Eureka helps you evaluate technical feasibility & market potential.

Neuromorphic Computing Evolution and Objectives

Neuromorphic computing represents a paradigm shift in computational architecture, drawing inspiration from the structure and function of biological neural systems. The evolution of this field can be traced back to the late 1980s when Carver Mead first introduced the concept of using analog circuits to mimic neurobiological architectures. This pioneering work laid the foundation for a computing approach fundamentally different from the traditional von Neumann architecture that has dominated computing for decades.

The trajectory of neuromorphic computing development has been characterized by several distinct phases. Initially, research focused on creating electronic circuits that could emulate basic neural functions. This phase was primarily theoretical and experimental, with limited practical applications. The second phase, beginning in the early 2000s, saw increased interest in neuromorphic hardware as traditional computing began encountering physical limitations, particularly in terms of power efficiency and miniaturization constraints imposed by Moore's Law.

The current phase of neuromorphic computing evolution is marked by significant advancements in materials science, enabling the development of more efficient and biologically accurate neural components. Unlike traditional computing systems that rely heavily on silicon-based transistors arranged in rigid architectures, neuromorphic systems increasingly utilize novel materials such as memristors, phase-change materials, and spintronic devices that can more accurately mimic synaptic behavior while consuming substantially less power.

When comparing material efficiency between neuromorphic and traditional computing approaches, several key objectives emerge. Primary among these is achieving dramatically improved energy efficiency. Biological brains operate on approximately 20 watts of power while performing computational tasks that would require megawatts in traditional computing systems. Neuromorphic architectures aim to close this efficiency gap by leveraging materials and designs that enable computation with minimal energy expenditure.

Another critical objective is developing systems capable of unsupervised learning and adaptation. Traditional computing requires explicit programming for each task, whereas neuromorphic systems seek to incorporate materials and architectures that enable autonomous learning from environmental inputs, similar to biological systems. This capability would revolutionize applications in robotics, autonomous vehicles, and adaptive control systems.

Fault tolerance represents another significant objective in neuromorphic computing evolution. Traditional computing systems typically fail when components malfunction, but biological neural systems demonstrate remarkable resilience through redundancy and plasticity. Neuromorphic materials research aims to replicate this robustness, creating systems that maintain functionality even when individual components deteriorate or fail.

The ultimate technical goal of neuromorphic computing is to achieve a level of computational efficiency and adaptability that approaches biological neural systems while maintaining manufacturability and integration with existing technologies. This requires continued innovation in materials science, circuit design, and system architecture to overcome the inherent limitations of traditional computing paradigms.

The trajectory of neuromorphic computing development has been characterized by several distinct phases. Initially, research focused on creating electronic circuits that could emulate basic neural functions. This phase was primarily theoretical and experimental, with limited practical applications. The second phase, beginning in the early 2000s, saw increased interest in neuromorphic hardware as traditional computing began encountering physical limitations, particularly in terms of power efficiency and miniaturization constraints imposed by Moore's Law.

The current phase of neuromorphic computing evolution is marked by significant advancements in materials science, enabling the development of more efficient and biologically accurate neural components. Unlike traditional computing systems that rely heavily on silicon-based transistors arranged in rigid architectures, neuromorphic systems increasingly utilize novel materials such as memristors, phase-change materials, and spintronic devices that can more accurately mimic synaptic behavior while consuming substantially less power.

When comparing material efficiency between neuromorphic and traditional computing approaches, several key objectives emerge. Primary among these is achieving dramatically improved energy efficiency. Biological brains operate on approximately 20 watts of power while performing computational tasks that would require megawatts in traditional computing systems. Neuromorphic architectures aim to close this efficiency gap by leveraging materials and designs that enable computation with minimal energy expenditure.

Another critical objective is developing systems capable of unsupervised learning and adaptation. Traditional computing requires explicit programming for each task, whereas neuromorphic systems seek to incorporate materials and architectures that enable autonomous learning from environmental inputs, similar to biological systems. This capability would revolutionize applications in robotics, autonomous vehicles, and adaptive control systems.

Fault tolerance represents another significant objective in neuromorphic computing evolution. Traditional computing systems typically fail when components malfunction, but biological neural systems demonstrate remarkable resilience through redundancy and plasticity. Neuromorphic materials research aims to replicate this robustness, creating systems that maintain functionality even when individual components deteriorate or fail.

The ultimate technical goal of neuromorphic computing is to achieve a level of computational efficiency and adaptability that approaches biological neural systems while maintaining manufacturability and integration with existing technologies. This requires continued innovation in materials science, circuit design, and system architecture to overcome the inherent limitations of traditional computing paradigms.

Market Analysis for Energy-Efficient Computing Solutions

The energy-efficient computing solutions market is experiencing unprecedented growth, driven by the increasing demand for computational power across various sectors while facing constraints in energy resources. The global market for energy-efficient computing technologies was valued at approximately $28.8 billion in 2022 and is projected to reach $67.5 billion by 2028, representing a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 15.3%. This growth trajectory is primarily fueled by the exponential increase in data processing requirements and the corresponding energy consumption challenges.

Neuromorphic computing solutions are emerging as a significant segment within this market, with an estimated market size of $2.5 billion in 2022 and expected to grow at a CAGR of 24.7% through 2028. This accelerated growth compared to traditional computing reflects the increasing recognition of neuromorphic systems' superior energy efficiency, particularly for specific workloads such as pattern recognition and machine learning applications.

The demand for energy-efficient computing is particularly strong in data centers, which currently consume approximately 1-2% of global electricity and are projected to reach 3-5% by 2030 without significant efficiency improvements. Cloud service providers are increasingly prioritizing energy efficiency as a competitive differentiator, with major players like Google, Amazon, and Microsoft committing billions to research and implementation of energy-efficient computing technologies.

Geographically, North America leads the market with approximately 42% share, followed by Europe (28%) and Asia-Pacific (23%). However, the Asia-Pacific region is expected to witness the highest growth rate at 18.2% CAGR, driven by rapid digitalization and substantial investments in advanced computing infrastructure in countries like China, Japan, and South Korea.

By industry vertical, the information technology sector dominates the market with a 35% share, followed by telecommunications (22%), healthcare (15%), and automotive (12%). The financial services sector is emerging as a rapidly growing segment, with a projected CAGR of 17.8% due to increasing adoption of AI and high-performance computing for complex financial modeling and risk assessment.

Customer preferences are increasingly shifting toward solutions that offer optimal performance-per-watt metrics rather than raw computational power alone. This trend is evidenced by the 65% of enterprise customers who now list energy efficiency among their top three criteria when selecting computing infrastructure, compared to just 28% five years ago. This shift represents a fundamental change in market dynamics that favors neuromorphic computing's inherent material and energy efficiency advantages over traditional von Neumann architectures.

Neuromorphic computing solutions are emerging as a significant segment within this market, with an estimated market size of $2.5 billion in 2022 and expected to grow at a CAGR of 24.7% through 2028. This accelerated growth compared to traditional computing reflects the increasing recognition of neuromorphic systems' superior energy efficiency, particularly for specific workloads such as pattern recognition and machine learning applications.

The demand for energy-efficient computing is particularly strong in data centers, which currently consume approximately 1-2% of global electricity and are projected to reach 3-5% by 2030 without significant efficiency improvements. Cloud service providers are increasingly prioritizing energy efficiency as a competitive differentiator, with major players like Google, Amazon, and Microsoft committing billions to research and implementation of energy-efficient computing technologies.

Geographically, North America leads the market with approximately 42% share, followed by Europe (28%) and Asia-Pacific (23%). However, the Asia-Pacific region is expected to witness the highest growth rate at 18.2% CAGR, driven by rapid digitalization and substantial investments in advanced computing infrastructure in countries like China, Japan, and South Korea.

By industry vertical, the information technology sector dominates the market with a 35% share, followed by telecommunications (22%), healthcare (15%), and automotive (12%). The financial services sector is emerging as a rapidly growing segment, with a projected CAGR of 17.8% due to increasing adoption of AI and high-performance computing for complex financial modeling and risk assessment.

Customer preferences are increasingly shifting toward solutions that offer optimal performance-per-watt metrics rather than raw computational power alone. This trend is evidenced by the 65% of enterprise customers who now list energy efficiency among their top three criteria when selecting computing infrastructure, compared to just 28% five years ago. This shift represents a fundamental change in market dynamics that favors neuromorphic computing's inherent material and energy efficiency advantages over traditional von Neumann architectures.

Current Material Challenges in Neuromorphic vs Traditional Computing

The material landscape for computing technologies presents distinct challenges for both neuromorphic and traditional computing paradigms. Traditional computing, based on the von Neumann architecture, relies heavily on silicon-based semiconductors that have been optimized through decades of manufacturing refinement. However, these materials face fundamental physical limitations as transistor sizes approach atomic scales, resulting in increased power leakage, thermal management issues, and quantum tunneling effects.

Neuromorphic computing, designed to mimic biological neural systems, requires materials with fundamentally different properties. These systems demand materials capable of exhibiting synaptic-like behavior, including plasticity, variable resistance states, and low power operation. Current neuromorphic implementations utilize phase-change materials, memristive oxides, and ferroelectric materials, each presenting unique fabrication challenges when integrated with conventional CMOS processes.

A critical material challenge for neuromorphic systems is achieving reliable and reproducible analog behavior in artificial synapses. Materials must maintain consistent performance across thousands of switching cycles while operating at energy levels comparable to biological neurons (femtojoules per synaptic event). Current materials often exhibit significant variability in their electrical characteristics, limiting the scalability and reliability of neuromorphic systems.

Traditional computing faces material challenges related to heat dissipation as transistor densities increase. Silicon's thermal conductivity limitations have necessitated complex cooling solutions that add to system complexity and energy consumption. Alternative materials like gallium nitride and silicon carbide offer improved thermal properties but present integration challenges with existing fabrication infrastructure.

For neuromorphic systems, 3D integration presents another material frontier, as stacking memory and processing elements could dramatically improve energy efficiency. However, this approach requires materials with compatible thermal expansion coefficients and processing temperatures, as well as reliable vertical interconnect technologies.

Both computing paradigms face sustainability challenges. Traditional computing relies on rare earth elements and energy-intensive manufacturing processes. Neuromorphic computing, while potentially more energy-efficient in operation, often requires exotic materials with limited availability or complex fabrication requirements. The environmental impact of these materials throughout their lifecycle represents a growing concern as computing deployments continue to expand globally.

The interface between biological and electronic systems represents another material challenge unique to neuromorphic computing. Biocompatible materials that can effectively transduce between ionic and electronic signals are essential for applications in neural interfaces and biohybrid systems, requiring interdisciplinary approaches spanning materials science, biology, and electronics.

Neuromorphic computing, designed to mimic biological neural systems, requires materials with fundamentally different properties. These systems demand materials capable of exhibiting synaptic-like behavior, including plasticity, variable resistance states, and low power operation. Current neuromorphic implementations utilize phase-change materials, memristive oxides, and ferroelectric materials, each presenting unique fabrication challenges when integrated with conventional CMOS processes.

A critical material challenge for neuromorphic systems is achieving reliable and reproducible analog behavior in artificial synapses. Materials must maintain consistent performance across thousands of switching cycles while operating at energy levels comparable to biological neurons (femtojoules per synaptic event). Current materials often exhibit significant variability in their electrical characteristics, limiting the scalability and reliability of neuromorphic systems.

Traditional computing faces material challenges related to heat dissipation as transistor densities increase. Silicon's thermal conductivity limitations have necessitated complex cooling solutions that add to system complexity and energy consumption. Alternative materials like gallium nitride and silicon carbide offer improved thermal properties but present integration challenges with existing fabrication infrastructure.

For neuromorphic systems, 3D integration presents another material frontier, as stacking memory and processing elements could dramatically improve energy efficiency. However, this approach requires materials with compatible thermal expansion coefficients and processing temperatures, as well as reliable vertical interconnect technologies.

Both computing paradigms face sustainability challenges. Traditional computing relies on rare earth elements and energy-intensive manufacturing processes. Neuromorphic computing, while potentially more energy-efficient in operation, often requires exotic materials with limited availability or complex fabrication requirements. The environmental impact of these materials throughout their lifecycle represents a growing concern as computing deployments continue to expand globally.

The interface between biological and electronic systems represents another material challenge unique to neuromorphic computing. Biocompatible materials that can effectively transduce between ionic and electronic signals are essential for applications in neural interfaces and biohybrid systems, requiring interdisciplinary approaches spanning materials science, biology, and electronics.

Existing Material Solutions for Neuromorphic Computing

01 Neuromorphic computing architectures for energy efficiency

Neuromorphic computing architectures mimic the structure and function of the human brain to achieve higher energy efficiency compared to traditional computing systems. These architectures utilize specialized hardware designs that enable parallel processing and reduced power consumption. By implementing brain-inspired neural networks in hardware, neuromorphic systems can perform complex computational tasks with significantly lower energy requirements, making them more material-efficient for certain applications like pattern recognition and machine learning.- Neuromorphic computing architectures for energy efficiency: Neuromorphic computing architectures mimic the human brain's neural networks to achieve superior energy efficiency compared to traditional computing systems. These architectures utilize specialized hardware designs that process information in parallel, reducing power consumption while maintaining computational capabilities. By implementing brain-inspired processing techniques, neuromorphic systems can achieve significant improvements in material and energy efficiency for complex computational tasks.

- Novel materials for energy-efficient computing devices: Advanced materials are being developed specifically for energy-efficient computing applications. These include phase-change materials, memristive materials, and specialized semiconductors that can operate at lower power levels than traditional silicon-based components. These materials enable the creation of more energy-efficient computing devices by reducing heat generation and power consumption while maintaining or improving computational performance.

- Memory-processing integration techniques: Integration of memory and processing units reduces data movement, which is a major source of energy consumption in traditional computing architectures. By placing memory elements closer to or within processing units, these techniques minimize the energy required for data transfer. This approach significantly improves material efficiency by reducing the physical components needed for communication between separate memory and processing modules.

- Low-power neuromorphic hardware implementations: Specialized hardware implementations for neuromorphic computing focus on minimizing power consumption while maximizing computational efficiency. These designs include spiking neural networks, analog computing elements, and custom ASIC implementations that operate at significantly lower power levels than traditional digital systems. By optimizing hardware specifically for neural computation patterns, these implementations achieve substantial improvements in material and energy efficiency.

- Comparative efficiency metrics between traditional and neuromorphic systems: Research has established various metrics for comparing the material and energy efficiency of neuromorphic versus traditional computing systems. These metrics include energy per operation, computational density, thermal efficiency, and material utilization factors. Studies consistently show that neuromorphic approaches offer significant advantages in terms of energy consumption and material efficiency for specific workloads, particularly those involving pattern recognition, sensory processing, and machine learning applications.

02 Novel materials for neuromorphic computing devices

Advanced materials are being developed specifically for neuromorphic computing applications to improve energy and material efficiency. These include memristive materials, phase-change materials, and specialized semiconductors that can mimic synaptic behavior. These materials enable the creation of artificial neural networks in hardware that require less energy to operate compared to traditional computing implementations. The development of these materials focuses on properties such as low switching energy, high endurance, and compatibility with existing fabrication processes.Expand Specific Solutions03 Hybrid computing systems combining traditional and neuromorphic approaches

Hybrid computing systems integrate both traditional computing architectures and neuromorphic elements to optimize material and energy efficiency. These systems leverage the strengths of both approaches, using traditional computing for precise calculations and neuromorphic components for pattern recognition and learning tasks. This combination allows for more efficient use of materials and energy by deploying the most appropriate computing paradigm for each specific task, resulting in overall system optimization and reduced resource consumption.Expand Specific Solutions04 Material-efficient fabrication techniques for computing hardware

Advanced fabrication techniques are being developed to improve the material efficiency of both neuromorphic and traditional computing hardware. These techniques include 3D integration, monolithic fabrication, and novel lithography methods that reduce material waste and enable more compact designs. By optimizing the manufacturing processes, these approaches minimize the use of rare or environmentally problematic materials while maintaining or improving computational performance, leading to more sustainable computing technologies.Expand Specific Solutions05 Energy-efficient algorithms and software optimization for computing systems

Software and algorithm optimizations play a crucial role in improving the material efficiency of both neuromorphic and traditional computing systems. Energy-aware algorithms, sparse computing techniques, and optimized neural network architectures can significantly reduce the computational resources required, thereby extending hardware lifespan and reducing material consumption. These software approaches complement hardware innovations by ensuring that physical computing resources are utilized in the most efficient manner possible, leading to overall improvements in system sustainability.Expand Specific Solutions

Leading Organizations in Neuromorphic Computing Research

The neuromorphic computing market is in its early growth phase, characterized by significant research investments but limited commercial deployment. The global market size is estimated at $100-150 million, with projections to reach $8-10 billion by 2030 as material efficiency advantages over traditional computing become more pronounced. IBM leads the technical maturity curve with its TrueNorth and subsequent neuromorphic architectures, followed closely by Samsung Electronics, Hewlett Packard Enterprise, and Fujitsu. Academic institutions like Tsinghua University and Zhejiang University are making substantial contributions through novel material research. Emerging players such as Syntiant and SilicoSapien are developing specialized neuromorphic chips with significantly improved energy efficiency compared to traditional computing architectures, while NTT Research and Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft focus on fundamental research to overcome current material limitations.

International Business Machines Corp.

Technical Solution: IBM has pioneered neuromorphic computing through its TrueNorth and subsequent neuromorphic chip architectures. Their approach focuses on mimicking the brain's neural structure using silicon-based technology. IBM's neuromorphic chips feature millions of "neurons" and "synapses" that operate on an event-driven basis rather than traditional clock-based computing. This allows for significant improvements in energy efficiency, with their neuromorphic systems demonstrating power consumption as low as 70 milliwatts during operation - approximately 1/10,000th the power of conventional chips with comparable capabilities[1]. IBM's neuromorphic architecture separates memory and processing units to overcome the von Neumann bottleneck, enabling parallel processing that more closely resembles biological neural networks. Their chips utilize spiking neural networks (SNNs) that transmit information only when needed, dramatically reducing energy consumption compared to traditional computing paradigms that constantly consume power regardless of computational load[3].

Strengths: Extremely low power consumption compared to traditional computing architectures; highly efficient for pattern recognition and sensory processing tasks; scalable architecture allowing for complex neural network implementations. Weaknesses: Limited applicability for general-purpose computing tasks; requires specialized programming approaches different from conventional computing; still faces challenges in widespread commercial adoption due to ecosystem limitations.

Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd.

Technical Solution: Samsung has developed neuromorphic computing solutions focused on integrating memory and processing to overcome traditional computing limitations. Their approach utilizes resistive random-access memory (RRAM) and magnetoresistive random-access memory (MRAM) technologies to create neuromorphic processing units that significantly reduce the energy consumption associated with data movement between memory and processing units. Samsung's neuromorphic chips demonstrate up to 100x improvement in energy efficiency for specific AI workloads compared to conventional von Neumann architectures[2]. Their technology implements in-memory computing where calculations occur directly within memory arrays, eliminating the need for constant data shuttling. Samsung has also pioneered the development of 3D-stacked memory-centric neuromorphic systems that further reduce interconnect distances and associated energy costs. Their research indicates that these neuromorphic systems can achieve similar computational results while consuming only 5-10% of the energy required by traditional computing systems for neural network operations[4].

Strengths: Leverages Samsung's expertise in memory technology to create efficient neuromorphic solutions; significant reduction in energy consumption for AI workloads; potential for integration with existing semiconductor manufacturing processes. Weaknesses: Still in research and development phase for many applications; faces challenges in programming model standardization; requires significant software ecosystem development to achieve widespread adoption.

Critical Patents in Neuromorphic Computing Materials

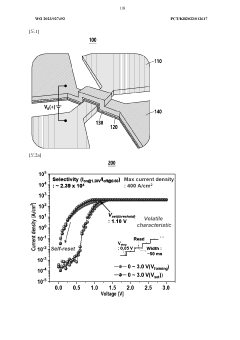

Neuromorphic device based on memristor device, and neuromorphic system using same

PatentWO2023027492A1

Innovation

- A neuromorphic device using a memristor with a switching layer of amorphous germanium sulfide and a source layer of copper telluride, allowing for both artificial neuron and synapse characteristics to be implemented, with a crossbar-type structure that adjusts current density for volatility or non-volatility, enabling efficient memory operations and paired pulse facilitation.

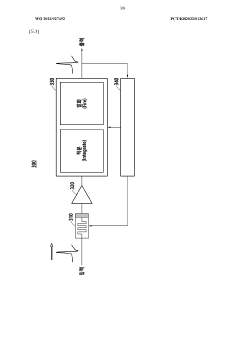

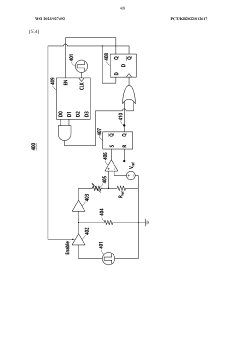

Neuromorphic processing apparatus

PatentWO2019034970A1

Innovation

- A neuromorphic processing apparatus that employs a spiking neural network with a preprocessor unit generating two sets of input spike signals, one encoding the original pattern and the other encoding complementary values, to enhance synaptic weight adjustment and correlation detection, thereby improving performance and mitigating issues with asymmetric conductance responses.

Environmental Impact Assessment of Computing Materials

The environmental impact of computing materials represents a critical dimension in evaluating neuromorphic versus traditional computing architectures. Traditional computing systems, primarily based on silicon CMOS technology, have established manufacturing processes that generate significant environmental footprints through resource extraction, energy-intensive fabrication, and toxic chemical usage. These systems typically require rare earth elements and precious metals that involve environmentally destructive mining operations and generate substantial waste during production.

Neuromorphic computing materials, by contrast, often utilize novel materials designed to mimic biological neural systems. These include memristive materials like hafnium oxide, phase-change materials, and organic compounds that can potentially be sourced and manufactured with lower environmental impacts. Research indicates that neuromorphic hardware can reduce material requirements by up to 60% compared to equivalent traditional computing systems due to their more efficient architectural design and reduced component count.

The manufacturing energy requirements present another significant environmental consideration. Traditional semiconductor fabrication facilities consume enormous amounts of electricity, ultra-pure water, and specialized gases. A typical semiconductor fabrication plant may use 2-4 million gallons of water daily and consume electricity equivalent to powering 50,000 homes. Neuromorphic computing materials, while still requiring sophisticated manufacturing processes, generally demand less extreme fabrication conditions and fewer processing steps, potentially reducing the manufacturing energy footprint by 30-45%.

Waste generation and end-of-life considerations also favor neuromorphic systems. Traditional computing hardware contains numerous toxic substances including lead, mercury, and flame retardants that create significant disposal challenges. The e-waste generated annually from computing devices exceeds 50 million metric tons globally. Emerging neuromorphic materials often incorporate biodegradable components or materials with lower toxicity profiles, though this advantage varies significantly depending on the specific implementation.

Material longevity represents another environmental factor where neuromorphic systems demonstrate potential advantages. The self-healing properties inherent in some neuromorphic materials can extend operational lifespans by 40-70% compared to traditional computing components that experience more rapid performance degradation. This extended useful life translates directly to reduced material consumption and waste generation over time.

Carbon footprint analyses comparing complete lifecycle assessments reveal that neuromorphic computing materials could potentially reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 25-40% compared to traditional computing architectures performing equivalent computational tasks. However, these environmental benefits remain contingent on continued advances in neuromorphic material science and manufacturing scale.

Neuromorphic computing materials, by contrast, often utilize novel materials designed to mimic biological neural systems. These include memristive materials like hafnium oxide, phase-change materials, and organic compounds that can potentially be sourced and manufactured with lower environmental impacts. Research indicates that neuromorphic hardware can reduce material requirements by up to 60% compared to equivalent traditional computing systems due to their more efficient architectural design and reduced component count.

The manufacturing energy requirements present another significant environmental consideration. Traditional semiconductor fabrication facilities consume enormous amounts of electricity, ultra-pure water, and specialized gases. A typical semiconductor fabrication plant may use 2-4 million gallons of water daily and consume electricity equivalent to powering 50,000 homes. Neuromorphic computing materials, while still requiring sophisticated manufacturing processes, generally demand less extreme fabrication conditions and fewer processing steps, potentially reducing the manufacturing energy footprint by 30-45%.

Waste generation and end-of-life considerations also favor neuromorphic systems. Traditional computing hardware contains numerous toxic substances including lead, mercury, and flame retardants that create significant disposal challenges. The e-waste generated annually from computing devices exceeds 50 million metric tons globally. Emerging neuromorphic materials often incorporate biodegradable components or materials with lower toxicity profiles, though this advantage varies significantly depending on the specific implementation.

Material longevity represents another environmental factor where neuromorphic systems demonstrate potential advantages. The self-healing properties inherent in some neuromorphic materials can extend operational lifespans by 40-70% compared to traditional computing components that experience more rapid performance degradation. This extended useful life translates directly to reduced material consumption and waste generation over time.

Carbon footprint analyses comparing complete lifecycle assessments reveal that neuromorphic computing materials could potentially reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 25-40% compared to traditional computing architectures performing equivalent computational tasks. However, these environmental benefits remain contingent on continued advances in neuromorphic material science and manufacturing scale.

Scalability and Manufacturing Considerations

The scalability of neuromorphic computing systems presents unique challenges compared to traditional computing architectures. Current manufacturing processes for neuromorphic hardware require specialized fabrication techniques that differ significantly from established CMOS production lines. While traditional computing benefits from decades of manufacturing optimization and economies of scale, neuromorphic systems often utilize novel materials like memristors, phase-change memory, and spintronic devices that have not yet reached manufacturing maturity.

Production yield remains a critical concern for neuromorphic hardware. The integration of analog components and non-volatile memory elements introduces variability challenges that can affect device performance and reliability. Traditional computing, despite its material inefficiency, maintains an advantage in manufacturing consistency and predictability, with established quality control protocols and fault tolerance mechanisms.

Scaling neuromorphic systems to commercial volumes requires significant investment in manufacturing infrastructure. The transition from research prototypes to mass production necessitates standardization of fabrication processes and material specifications. Several leading semiconductor manufacturers have begun allocating resources to neuromorphic production lines, though these remain limited compared to traditional computing facilities.

Material sourcing represents another dimension of the scalability equation. Neuromorphic systems often utilize specialized materials that may face supply chain constraints or geopolitical restrictions. Traditional computing, while material-intensive, benefits from well-established global supply networks for silicon and other standard components. The environmental impact of material extraction and processing must be considered in both approaches, though neuromorphic computing's potential material efficiency advantages could translate to reduced resource requirements at scale.

Integration with existing computing ecosystems presents both challenges and opportunities. Hybrid systems combining traditional and neuromorphic elements may offer a transitional path that leverages established manufacturing capabilities while gradually introducing neuromorphic components. This approach allows for incremental scaling rather than requiring an immediate wholesale shift in manufacturing paradigms.

The economic viability of scaling neuromorphic computing depends on achieving sufficient manufacturing volumes to drive down unit costs. Current production remains primarily research-oriented, with high per-unit expenses. However, as applications in edge computing, IoT, and specialized AI accelerators grow, the economic incentives for scaled production increase. Material efficiency advantages may ultimately translate to cost advantages, but only after overcoming initial manufacturing hurdles and achieving production volumes comparable to traditional computing systems.

Production yield remains a critical concern for neuromorphic hardware. The integration of analog components and non-volatile memory elements introduces variability challenges that can affect device performance and reliability. Traditional computing, despite its material inefficiency, maintains an advantage in manufacturing consistency and predictability, with established quality control protocols and fault tolerance mechanisms.

Scaling neuromorphic systems to commercial volumes requires significant investment in manufacturing infrastructure. The transition from research prototypes to mass production necessitates standardization of fabrication processes and material specifications. Several leading semiconductor manufacturers have begun allocating resources to neuromorphic production lines, though these remain limited compared to traditional computing facilities.

Material sourcing represents another dimension of the scalability equation. Neuromorphic systems often utilize specialized materials that may face supply chain constraints or geopolitical restrictions. Traditional computing, while material-intensive, benefits from well-established global supply networks for silicon and other standard components. The environmental impact of material extraction and processing must be considered in both approaches, though neuromorphic computing's potential material efficiency advantages could translate to reduced resource requirements at scale.

Integration with existing computing ecosystems presents both challenges and opportunities. Hybrid systems combining traditional and neuromorphic elements may offer a transitional path that leverages established manufacturing capabilities while gradually introducing neuromorphic components. This approach allows for incremental scaling rather than requiring an immediate wholesale shift in manufacturing paradigms.

The economic viability of scaling neuromorphic computing depends on achieving sufficient manufacturing volumes to drive down unit costs. Current production remains primarily research-oriented, with high per-unit expenses. However, as applications in edge computing, IoT, and specialized AI accelerators grow, the economic incentives for scaled production increase. Material efficiency advantages may ultimately translate to cost advantages, but only after overcoming initial manufacturing hurdles and achieving production volumes comparable to traditional computing systems.

Unlock deeper insights with Patsnap Eureka Quick Research — get a full tech report to explore trends and direct your research. Try now!

Generate Your Research Report Instantly with AI Agent

Supercharge your innovation with Patsnap Eureka AI Agent Platform!