Comparison of Microreactors in Academic vs Industrial Use Cases

SEP 24, 202510 MIN READ

Generate Your Research Report Instantly with AI Agent

Patsnap Eureka helps you evaluate technical feasibility & market potential.

Microreactor Technology Evolution and Objectives

Microreactor technology has evolved significantly over the past several decades, transitioning from simple laboratory devices to sophisticated industrial systems. The concept of microreactors emerged in the 1980s with early experiments in miniaturized reaction vessels, but gained substantial momentum in the late 1990s with advances in microfabrication techniques. This evolution has been driven by the fundamental advantages microreactors offer: enhanced heat and mass transfer, improved reaction control, reduced reagent consumption, and increased safety profiles.

The academic development of microreactors initially focused on proof-of-concept studies demonstrating superior mixing characteristics and reaction efficiency compared to conventional batch reactors. By the early 2000s, academic research expanded to explore various materials for microreactor construction, including glass, silicon, metals, and polymers, each offering distinct advantages for specific reaction types and conditions.

Industrial adoption followed a different trajectory, with early applications primarily in pharmaceutical and fine chemical production. The transition from academic to industrial settings required addressing scale-up challenges, durability concerns, and integration with existing manufacturing processes. This divergence in development paths has created distinct technological lineages in academic versus industrial microreactor designs.

Current technological objectives in academic settings predominantly center on pushing the boundaries of reaction conditions, exploring novel catalyst integration methods, and developing multi-functional microreactor systems. Academic researchers are increasingly focused on microreactor applications for emerging fields such as nanomaterial synthesis, biocatalysis, and continuous-flow organic synthesis.

In contrast, industrial objectives emphasize reliability, scalability, and economic viability. Industrial microreactor development targets process intensification, modular manufacturing capabilities, and integration with digital control systems for real-time monitoring and optimization. The pharmaceutical industry, in particular, has embraced microreactor technology to implement continuous manufacturing processes that align with Quality by Design (QbD) principles.

Looking forward, the convergence of academic innovation and industrial practicality represents a critical objective for microreactor technology advancement. Bridging this gap requires collaborative efforts to translate fundamental research into commercially viable solutions. Emerging objectives include developing standardized microreactor platforms that can serve both research and production needs, creating more accessible design and simulation tools, and establishing comprehensive performance metrics that facilitate technology transfer between academic and industrial settings.

The evolution trajectory suggests that future microreactor development will increasingly focus on sustainability aspects, including energy efficiency, reduced environmental footprint, and compatibility with green chemistry principles. This alignment of technological capabilities with broader societal goals represents an important dimension in the ongoing evolution of microreactor technology.

The academic development of microreactors initially focused on proof-of-concept studies demonstrating superior mixing characteristics and reaction efficiency compared to conventional batch reactors. By the early 2000s, academic research expanded to explore various materials for microreactor construction, including glass, silicon, metals, and polymers, each offering distinct advantages for specific reaction types and conditions.

Industrial adoption followed a different trajectory, with early applications primarily in pharmaceutical and fine chemical production. The transition from academic to industrial settings required addressing scale-up challenges, durability concerns, and integration with existing manufacturing processes. This divergence in development paths has created distinct technological lineages in academic versus industrial microreactor designs.

Current technological objectives in academic settings predominantly center on pushing the boundaries of reaction conditions, exploring novel catalyst integration methods, and developing multi-functional microreactor systems. Academic researchers are increasingly focused on microreactor applications for emerging fields such as nanomaterial synthesis, biocatalysis, and continuous-flow organic synthesis.

In contrast, industrial objectives emphasize reliability, scalability, and economic viability. Industrial microreactor development targets process intensification, modular manufacturing capabilities, and integration with digital control systems for real-time monitoring and optimization. The pharmaceutical industry, in particular, has embraced microreactor technology to implement continuous manufacturing processes that align with Quality by Design (QbD) principles.

Looking forward, the convergence of academic innovation and industrial practicality represents a critical objective for microreactor technology advancement. Bridging this gap requires collaborative efforts to translate fundamental research into commercially viable solutions. Emerging objectives include developing standardized microreactor platforms that can serve both research and production needs, creating more accessible design and simulation tools, and establishing comprehensive performance metrics that facilitate technology transfer between academic and industrial settings.

The evolution trajectory suggests that future microreactor development will increasingly focus on sustainability aspects, including energy efficiency, reduced environmental footprint, and compatibility with green chemistry principles. This alignment of technological capabilities with broader societal goals represents an important dimension in the ongoing evolution of microreactor technology.

Market Applications and Demand Analysis

The microreactor market has witnessed significant growth in recent years, driven by increasing demand across various industries. The global microreactor technology market was valued at approximately $1.2 billion in 2022 and is projected to grow at a CAGR of 9.8% through 2030, reflecting the expanding applications and adoption of this technology.

In academic settings, microreactors are primarily utilized for research purposes, focusing on reaction optimization, catalyst screening, and process development. The academic market segment is characterized by smaller-scale operations with emphasis on flexibility and versatility rather than throughput. Universities and research institutions represent the primary customers, with funding typically coming from government grants, academic budgets, and industry collaborations.

Industrial applications of microreactors span multiple sectors including pharmaceuticals, fine chemicals, petrochemicals, and specialty materials. The pharmaceutical industry represents the largest market share at roughly 35%, where microreactors enable continuous manufacturing processes, improving product quality and reducing time-to-market for new drugs. The fine chemicals sector follows at approximately 28% market share, valuing precise reaction control and enhanced safety profiles.

Regional analysis reveals that North America currently leads the microreactor market with approximately 38% share, followed by Europe (32%) and Asia-Pacific (25%). However, the Asia-Pacific region is experiencing the fastest growth rate, driven by rapid industrialization in countries like China and India, and increasing investments in pharmaceutical manufacturing infrastructure.

Key market drivers include stringent regulatory requirements for product quality and safety, particularly in pharmaceutical manufacturing, where continuous processing using microreactors offers better control and documentation. Additionally, sustainability concerns are pushing industries toward more efficient processes with reduced waste generation and energy consumption, which microreactors effectively address.

The demand for customized microreactor solutions is growing, with end-users seeking systems tailored to specific applications rather than generic platforms. This trend is creating opportunities for specialized equipment manufacturers and technology providers who can deliver application-specific solutions.

Market barriers include high initial investment costs, technical expertise requirements for implementation, and integration challenges with existing manufacturing infrastructure. These factors particularly affect small and medium-sized enterprises, limiting broader market penetration despite the clear technical advantages of microreactor technology.

Future market growth is expected to be driven by increasing adoption in emerging applications such as biopharmaceuticals, nanomaterials synthesis, and renewable energy technologies, where precise reaction control and scalability are critical requirements.

In academic settings, microreactors are primarily utilized for research purposes, focusing on reaction optimization, catalyst screening, and process development. The academic market segment is characterized by smaller-scale operations with emphasis on flexibility and versatility rather than throughput. Universities and research institutions represent the primary customers, with funding typically coming from government grants, academic budgets, and industry collaborations.

Industrial applications of microreactors span multiple sectors including pharmaceuticals, fine chemicals, petrochemicals, and specialty materials. The pharmaceutical industry represents the largest market share at roughly 35%, where microreactors enable continuous manufacturing processes, improving product quality and reducing time-to-market for new drugs. The fine chemicals sector follows at approximately 28% market share, valuing precise reaction control and enhanced safety profiles.

Regional analysis reveals that North America currently leads the microreactor market with approximately 38% share, followed by Europe (32%) and Asia-Pacific (25%). However, the Asia-Pacific region is experiencing the fastest growth rate, driven by rapid industrialization in countries like China and India, and increasing investments in pharmaceutical manufacturing infrastructure.

Key market drivers include stringent regulatory requirements for product quality and safety, particularly in pharmaceutical manufacturing, where continuous processing using microreactors offers better control and documentation. Additionally, sustainability concerns are pushing industries toward more efficient processes with reduced waste generation and energy consumption, which microreactors effectively address.

The demand for customized microreactor solutions is growing, with end-users seeking systems tailored to specific applications rather than generic platforms. This trend is creating opportunities for specialized equipment manufacturers and technology providers who can deliver application-specific solutions.

Market barriers include high initial investment costs, technical expertise requirements for implementation, and integration challenges with existing manufacturing infrastructure. These factors particularly affect small and medium-sized enterprises, limiting broader market penetration despite the clear technical advantages of microreactor technology.

Future market growth is expected to be driven by increasing adoption in emerging applications such as biopharmaceuticals, nanomaterials synthesis, and renewable energy technologies, where precise reaction control and scalability are critical requirements.

Current Challenges in Academic and Industrial Microreactors

Despite significant advancements in microreactor technology, both academic and industrial applications face distinct challenges that hinder optimal implementation and widespread adoption. In academic settings, researchers struggle with limited funding for high-quality equipment, resulting in compromises on materials, sensors, and control systems. This financial constraint often leads to less robust designs that may not withstand extended operation periods or aggressive reaction conditions, potentially affecting experimental reproducibility and data reliability.

Academic microreactors frequently suffer from scalability issues, as they are typically designed for proof-of-concept demonstrations rather than volume production. When successful reactions need scaling up, researchers encounter significant challenges in maintaining reaction parameters and performance across different reactor sizes. Additionally, academic institutions often lack specialized technical support staff for microreactor maintenance and troubleshooting, leading to operational inefficiencies and extended downtime periods.

In industrial environments, microreactors face different but equally significant challenges. Integration with existing manufacturing infrastructure presents substantial difficulties, as companies must adapt established processes and equipment to accommodate microreactor technology. This integration often requires significant capital investment and process redesign, creating resistance to adoption despite potential long-term benefits.

Regulatory compliance represents another major hurdle for industrial microreactor implementation. Pharmaceutical and chemical industries must navigate complex validation requirements and documentation processes when introducing new manufacturing technologies. The novelty of microreactor technology means that regulatory frameworks may not be fully developed, creating uncertainty in compliance pathways and potentially extending time-to-market.

Both sectors struggle with knowledge transfer barriers. Academic innovations often remain confined to research papers without practical implementation guides, while industrial developments may be protected as trade secrets. This compartmentalization impedes cross-sector learning and slows overall technology advancement. Furthermore, standardization remains underdeveloped, with various designs, materials, and operational protocols creating compatibility issues and hindering broader adoption.

Material limitations affect both sectors, with microchannels susceptible to fouling, clogging, and corrosion during extended operation. While industrial settings may invest in advanced materials and cleaning protocols, academic researchers often lack resources for such solutions, compromising experimental longevity and reliability. Additionally, both sectors face challenges in real-time monitoring and control at microscale, though industrial applications typically have more sophisticated instrumentation capabilities.

Addressing these challenges requires collaborative approaches between academia and industry, including joint development initiatives, standardization efforts, and improved knowledge sharing platforms to accelerate microreactor technology maturation and widespread implementation.

Academic microreactors frequently suffer from scalability issues, as they are typically designed for proof-of-concept demonstrations rather than volume production. When successful reactions need scaling up, researchers encounter significant challenges in maintaining reaction parameters and performance across different reactor sizes. Additionally, academic institutions often lack specialized technical support staff for microreactor maintenance and troubleshooting, leading to operational inefficiencies and extended downtime periods.

In industrial environments, microreactors face different but equally significant challenges. Integration with existing manufacturing infrastructure presents substantial difficulties, as companies must adapt established processes and equipment to accommodate microreactor technology. This integration often requires significant capital investment and process redesign, creating resistance to adoption despite potential long-term benefits.

Regulatory compliance represents another major hurdle for industrial microreactor implementation. Pharmaceutical and chemical industries must navigate complex validation requirements and documentation processes when introducing new manufacturing technologies. The novelty of microreactor technology means that regulatory frameworks may not be fully developed, creating uncertainty in compliance pathways and potentially extending time-to-market.

Both sectors struggle with knowledge transfer barriers. Academic innovations often remain confined to research papers without practical implementation guides, while industrial developments may be protected as trade secrets. This compartmentalization impedes cross-sector learning and slows overall technology advancement. Furthermore, standardization remains underdeveloped, with various designs, materials, and operational protocols creating compatibility issues and hindering broader adoption.

Material limitations affect both sectors, with microchannels susceptible to fouling, clogging, and corrosion during extended operation. While industrial settings may invest in advanced materials and cleaning protocols, academic researchers often lack resources for such solutions, compromising experimental longevity and reliability. Additionally, both sectors face challenges in real-time monitoring and control at microscale, though industrial applications typically have more sophisticated instrumentation capabilities.

Addressing these challenges requires collaborative approaches between academia and industry, including joint development initiatives, standardization efforts, and improved knowledge sharing platforms to accelerate microreactor technology maturation and widespread implementation.

Contemporary Microreactor Implementation Strategies

01 Microreactor design and fabrication

Microreactors are designed and fabricated using various materials and techniques to create miniaturized reaction vessels. These designs often incorporate channels, mixing zones, and controlled environments for chemical reactions. The fabrication methods include micromachining, etching, and advanced manufacturing techniques that allow for precise control of reactor geometry and surface properties, enabling efficient heat and mass transfer at the microscale.- Design and fabrication of microreactors: Microreactors are miniaturized reaction systems with dimensions in the micrometer range. The design and fabrication of these devices involve various materials and techniques to create microchannels, mixing zones, and reaction chambers. Advanced manufacturing methods such as micromachining, lithography, and 3D printing are employed to create precise microstructures. These designs often incorporate features for enhanced mixing, heat transfer, and controlled residence time to improve reaction efficiency.

- Chemical synthesis applications in microreactors: Microreactors offer significant advantages for chemical synthesis processes, including improved control over reaction parameters, enhanced safety for hazardous reactions, and increased yield and selectivity. These devices enable precise temperature control, efficient mixing, and reduced reaction times. They are particularly valuable for multiphase reactions, catalytic processes, and the synthesis of fine chemicals and pharmaceuticals. The controlled environment allows for optimization of reaction conditions and scaling through numbering-up rather than traditional scale-up.

- Microfluidic systems for biological applications: Microreactors designed for biological applications incorporate specialized features for cell culture, enzymatic reactions, and biomolecular analysis. These systems can maintain viable cellular environments, perform high-throughput screening, and enable precise manipulation of biological samples. Applications include point-of-care diagnostics, drug discovery, tissue engineering, and personalized medicine. The controlled microenvironment allows for mimicking in vivo conditions and studying cellular responses with minimal sample consumption.

- Flow control and mixing technologies in microreactors: Advanced flow control and mixing technologies are essential components of microreactor systems. These include passive mixing structures (such as baffles, zigzag channels, and split-and-recombine elements) and active mixing methods (using acoustic, electrical, or magnetic forces). Precise flow control is achieved through micropumps, valves, and pressure regulators. These technologies enable efficient mass and heat transfer, reduced diffusion limitations, and controlled residence time distribution, which are critical for reaction performance and reproducibility.

- Scale-up and industrial implementation of microreactor technology: The transition from laboratory-scale microreactors to industrial production involves strategies for increasing throughput while maintaining the advantages of microscale processing. This is typically achieved through numbering-up (parallel operation of multiple microreactors) rather than traditional scale-up. Industrial implementation requires addressing challenges related to reliability, robustness, maintenance, and integration with existing processes. Continuous flow manufacturing using microreactor technology offers benefits including reduced footprint, improved safety, and enhanced process control for various industries.

02 Chemical synthesis applications in microreactors

Microreactors are utilized for various chemical synthesis applications, offering advantages such as enhanced reaction control, improved yields, and reduced waste. These systems enable precise control over reaction parameters including temperature, pressure, and residence time, making them suitable for complex chemical transformations, continuous flow chemistry, and the production of specialty chemicals under safer and more efficient conditions.Expand Specific Solutions03 Microfluidic systems for biological applications

Microreactors are employed in biological applications, including cell culture, enzymatic reactions, and diagnostic assays. These microfluidic systems provide controlled environments for biological processes, enabling high-throughput screening, point-of-care diagnostics, and personalized medicine approaches. The small volumes required reduce reagent consumption and allow for parallel processing of multiple samples simultaneously.Expand Specific Solutions04 Process intensification and scale-up strategies

Microreactors facilitate process intensification by enhancing heat and mass transfer, allowing for more efficient and safer chemical processes. Scale-up strategies include numbering-up (parallel operation of multiple microreactors) rather than traditional size scaling, maintaining the advantageous characteristics of the microscale while increasing production capacity. This approach enables consistent product quality and process parameters from laboratory to industrial scale.Expand Specific Solutions05 Integration of monitoring and control systems

Advanced monitoring and control systems are integrated into microreactor technology to enable real-time process analysis and automation. These systems incorporate sensors, analytical tools, and feedback mechanisms that allow for continuous monitoring of reaction parameters and product quality. The integration of these technologies facilitates process optimization, quality control, and the implementation of artificial intelligence for adaptive process management.Expand Specific Solutions

Leading Organizations and Competitive Landscape

The microreactor technology landscape is currently in a growth phase, with an estimated market size of $1.2-1.5 billion and projected annual growth of 8-10%. The competitive landscape reveals a distinct divide between academic and industrial applications. Academic institutions like Vanderbilt University, Technical University of Denmark, and Jiangnan University focus on fundamental research and novel applications, while industrial players have developed more mature commercial implementations. Companies like Corning, Lonza, and Becton Dickinson have established strong positions in pharmaceutical applications, whereas Sinopec and China Petroleum & Chemical Corp. lead in petrochemical applications. The technology shows varying maturity levels across sectors, with pharmaceutical applications being more advanced than emerging fields like sustainable chemistry, where companies like DSM and Arkema are making significant investments.

Corning, Inc.

Technical Solution: Corning has developed advanced glass microreactor systems that leverage their expertise in specialty glass and ceramics. Their Advanced-Flow™ Reactor (AFR) technology represents a significant industrial application of microreactors, featuring high chemical resistance, excellent heat transfer capabilities, and modular design. The AFR system utilizes specially designed fluidic modules with heart-shaped mixing chambers that ensure efficient mixing and precise residence time control. Corning's microreactors can handle multiphase reactions (liquid-liquid, gas-liquid) and operate under high pressure (up to 18 bar) and temperature conditions (up to 200°C), making them suitable for a wide range of chemical processes including hazardous and highly exothermic reactions[1]. Their industrial implementation focuses on continuous flow chemistry for pharmaceutical and fine chemical manufacturing, with demonstrated scale-up capabilities from lab to production volumes.

Strengths: Superior heat transfer capabilities allowing for better temperature control in exothermic reactions; excellent chemical resistance; proven scalability from laboratory to production; modular design enabling flexible configuration. Weaknesses: Higher capital investment compared to traditional batch reactors; requires specialized expertise for implementation; limited to certain reaction types and conditions; potential challenges with solids handling.

Lonza Ltd.

Technical Solution: Lonza has pioneered industrial microreactor technology through their FlowPlate® microreactor systems, specifically designed for pharmaceutical and fine chemical manufacturing. Their approach integrates microreactor technology with continuous flow processing to address challenges in API production and hazardous chemistry. Lonza's microreactor systems feature precision-engineered microchannels (typically 200-500 μm) that maximize surface-to-volume ratios, enabling intensified heat and mass transfer rates up to 100 times greater than conventional reactors[2]. The company has successfully implemented this technology for commercial-scale production of pharmaceutical intermediates, demonstrating yield improvements of 20-30% and significant reduction in reaction times from hours to minutes. Lonza's systems incorporate real-time analytical monitoring and automated control systems that ensure consistent product quality and enable rapid process optimization, representing a significant advancement over academic microreactor implementations that often lack such integrated capabilities.

Strengths: Proven track record in commercial pharmaceutical manufacturing; integrated analytical capabilities for real-time process monitoring; demonstrated yield improvements and reaction time reductions; expertise in regulatory compliance for pharmaceutical production. Weaknesses: High initial capital investment; requires specialized operator training; limited flexibility for rapid process changes; challenges with certain multiphase reactions and solid-forming processes.

Key Patents and Scientific Breakthroughs

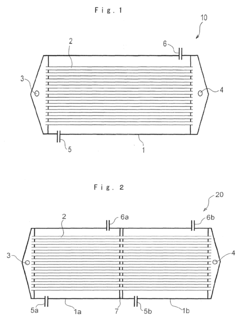

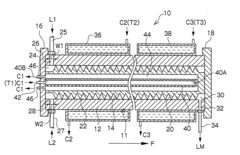

Process for producing radical polymer and microapparatus for chemical reaction

PatentInactiveEP1650228A1

Innovation

- A method involving a reaction microtube with an inner diameter of 2 mm or less, where a radical polymerization initiator and monomer are fed under flow conditions, and the polymerization temperature is controlled using a temperature-regulating jacket with independently controlled sections, ensuring laminar flow and uniform temperature.

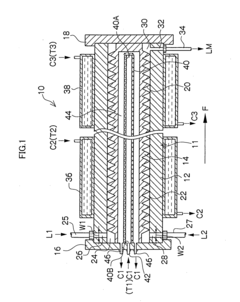

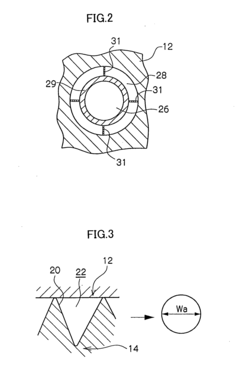

Microreactor

PatentInactiveUS20050031507A1

Innovation

- A microreactor with a spiral reaction channel formed by cutting a spiral screw thread on a round-bar-shaped core member or an outer cylindrical member, allowing for easy and robust manufacturing using general machining technologies, eliminating the need for special precision micro processing techniques.

Scale-up Considerations and Process Integration

The transition from academic microreactor applications to industrial implementation presents significant scale-up challenges that must be addressed systematically. Academic microreactors typically operate at milliliter or even microliter volumes, while industrial applications require throughput measured in tons per day. This volume disparity necessitates either massive parallelization (numbering-up) or dimensional scaling (scaling-out) strategies, each with distinct engineering considerations.

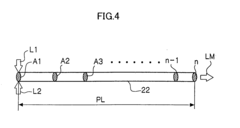

Numbering-up approaches maintain the fundamental microreactor dimensions while increasing quantity, preserving the advantageous heat and mass transfer characteristics. However, this strategy introduces complex flow distribution challenges across parallel units. Industrial implementations must incorporate sophisticated manifold designs to ensure uniform pressure drops and residence times across all channels, preventing product quality variations.

Dimensional scaling alternatively increases channel dimensions while maintaining laminar flow regimes, but sacrifices some of the inherent advantages of microscale operations. The critical Reynolds number threshold must be carefully monitored to preserve desired mixing characteristics while increasing throughput.

Process integration represents another fundamental consideration when transitioning microreactor technology from laboratory to production environments. Academic setups typically operate as standalone units with manual intervention, while industrial applications require seamless integration with upstream and downstream processes. This necessitates robust automation systems, real-time monitoring capabilities, and control algorithms that can maintain process stability despite fluctuations.

Material selection diverges significantly between academic and industrial contexts. While academic prototypes often utilize glass, silicon, or polymeric materials for ease of fabrication and observation, industrial implementations demand materials with superior chemical resistance, thermal stability, and mechanical durability. Stainless steel, specialized alloys, and ceramic materials predominate in industrial microreactor systems, necessitating different fabrication techniques and connection technologies.

Continuous operation requirements further differentiate industrial implementations. While academic studies may run for hours, industrial systems must operate reliably for months between maintenance intervals. This demands enhanced fouling resistance, cleaning-in-place capabilities, and redundant systems to prevent costly production interruptions.

Economic considerations ultimately drive industrial adoption decisions. The capital expenditure for microreactor implementation must be justified through process intensification benefits, including improved yield, selectivity, safety, and reduced footprint. Comprehensive techno-economic analysis comparing conventional batch processes with microreactor alternatives becomes essential for investment decisions, with particular attention to maintenance requirements, operational flexibility, and lifecycle costs.

Numbering-up approaches maintain the fundamental microreactor dimensions while increasing quantity, preserving the advantageous heat and mass transfer characteristics. However, this strategy introduces complex flow distribution challenges across parallel units. Industrial implementations must incorporate sophisticated manifold designs to ensure uniform pressure drops and residence times across all channels, preventing product quality variations.

Dimensional scaling alternatively increases channel dimensions while maintaining laminar flow regimes, but sacrifices some of the inherent advantages of microscale operations. The critical Reynolds number threshold must be carefully monitored to preserve desired mixing characteristics while increasing throughput.

Process integration represents another fundamental consideration when transitioning microreactor technology from laboratory to production environments. Academic setups typically operate as standalone units with manual intervention, while industrial applications require seamless integration with upstream and downstream processes. This necessitates robust automation systems, real-time monitoring capabilities, and control algorithms that can maintain process stability despite fluctuations.

Material selection diverges significantly between academic and industrial contexts. While academic prototypes often utilize glass, silicon, or polymeric materials for ease of fabrication and observation, industrial implementations demand materials with superior chemical resistance, thermal stability, and mechanical durability. Stainless steel, specialized alloys, and ceramic materials predominate in industrial microreactor systems, necessitating different fabrication techniques and connection technologies.

Continuous operation requirements further differentiate industrial implementations. While academic studies may run for hours, industrial systems must operate reliably for months between maintenance intervals. This demands enhanced fouling resistance, cleaning-in-place capabilities, and redundant systems to prevent costly production interruptions.

Economic considerations ultimately drive industrial adoption decisions. The capital expenditure for microreactor implementation must be justified through process intensification benefits, including improved yield, selectivity, safety, and reduced footprint. Comprehensive techno-economic analysis comparing conventional batch processes with microreactor alternatives becomes essential for investment decisions, with particular attention to maintenance requirements, operational flexibility, and lifecycle costs.

Economic Feasibility and ROI Analysis

The economic analysis of microreactors reveals significant differences between academic and industrial applications. In academic settings, microreactors typically represent lower initial investments, ranging from $5,000 to $50,000 for basic setups, with funding often secured through research grants or institutional budgets. These systems prioritize flexibility and research capabilities over long-term economic returns, with ROI measured primarily through research outputs, publications, and educational value rather than direct financial gains.

Industrial implementations, conversely, require substantially higher capital expenditures, typically between $100,000 and several million dollars for fully integrated systems. These investments demand rigorous financial justification through traditional ROI metrics. Analysis shows that industrial microreactors can achieve payback periods of 2-5 years, with ROI rates of 15-30% being common for successful implementations. The economic advantages stem primarily from reduced waste generation (30-50% reduction compared to batch processes), lower energy consumption (20-40% savings), and decreased solvent usage (up to 60% reduction).

Operational economics further differentiate the two contexts. Academic microreactors typically operate intermittently with higher per-run costs but lower overall operational budgets. Industrial systems benefit from economies of scale, with continuous operation significantly reducing per-unit production costs despite higher maintenance requirements. Labor costs also differ substantially, with academic settings utilizing student researchers and technical staff, while industrial applications require specialized operators commanding higher salaries but managing larger production volumes.

Risk assessment reveals that academic projects face lower financial consequences from experimental failures, allowing greater exploration of novel chemistries and processes. Industrial implementations must contend with more significant financial risks, including production downtime and potential product quality issues, necessitating more conservative approaches to implementation and process changes.

The scalability factor presents perhaps the most critical economic consideration. Academic microreactors rarely need to demonstrate commercial scalability, while industrial applications must prove economic viability at production scales. Numbering-up approaches (adding parallel reactors) typically increase costs linearly, while traditional scale-up benefits from non-linear cost advantages. This fundamental difference significantly impacts long-term economic feasibility calculations and often represents the most challenging transition from academic to industrial implementation.

Industrial implementations, conversely, require substantially higher capital expenditures, typically between $100,000 and several million dollars for fully integrated systems. These investments demand rigorous financial justification through traditional ROI metrics. Analysis shows that industrial microreactors can achieve payback periods of 2-5 years, with ROI rates of 15-30% being common for successful implementations. The economic advantages stem primarily from reduced waste generation (30-50% reduction compared to batch processes), lower energy consumption (20-40% savings), and decreased solvent usage (up to 60% reduction).

Operational economics further differentiate the two contexts. Academic microreactors typically operate intermittently with higher per-run costs but lower overall operational budgets. Industrial systems benefit from economies of scale, with continuous operation significantly reducing per-unit production costs despite higher maintenance requirements. Labor costs also differ substantially, with academic settings utilizing student researchers and technical staff, while industrial applications require specialized operators commanding higher salaries but managing larger production volumes.

Risk assessment reveals that academic projects face lower financial consequences from experimental failures, allowing greater exploration of novel chemistries and processes. Industrial implementations must contend with more significant financial risks, including production downtime and potential product quality issues, necessitating more conservative approaches to implementation and process changes.

The scalability factor presents perhaps the most critical economic consideration. Academic microreactors rarely need to demonstrate commercial scalability, while industrial applications must prove economic viability at production scales. Numbering-up approaches (adding parallel reactors) typically increase costs linearly, while traditional scale-up benefits from non-linear cost advantages. This fundamental difference significantly impacts long-term economic feasibility calculations and often represents the most challenging transition from academic to industrial implementation.

Unlock deeper insights with Patsnap Eureka Quick Research — get a full tech report to explore trends and direct your research. Try now!

Generate Your Research Report Instantly with AI Agent

Supercharge your innovation with Patsnap Eureka AI Agent Platform!