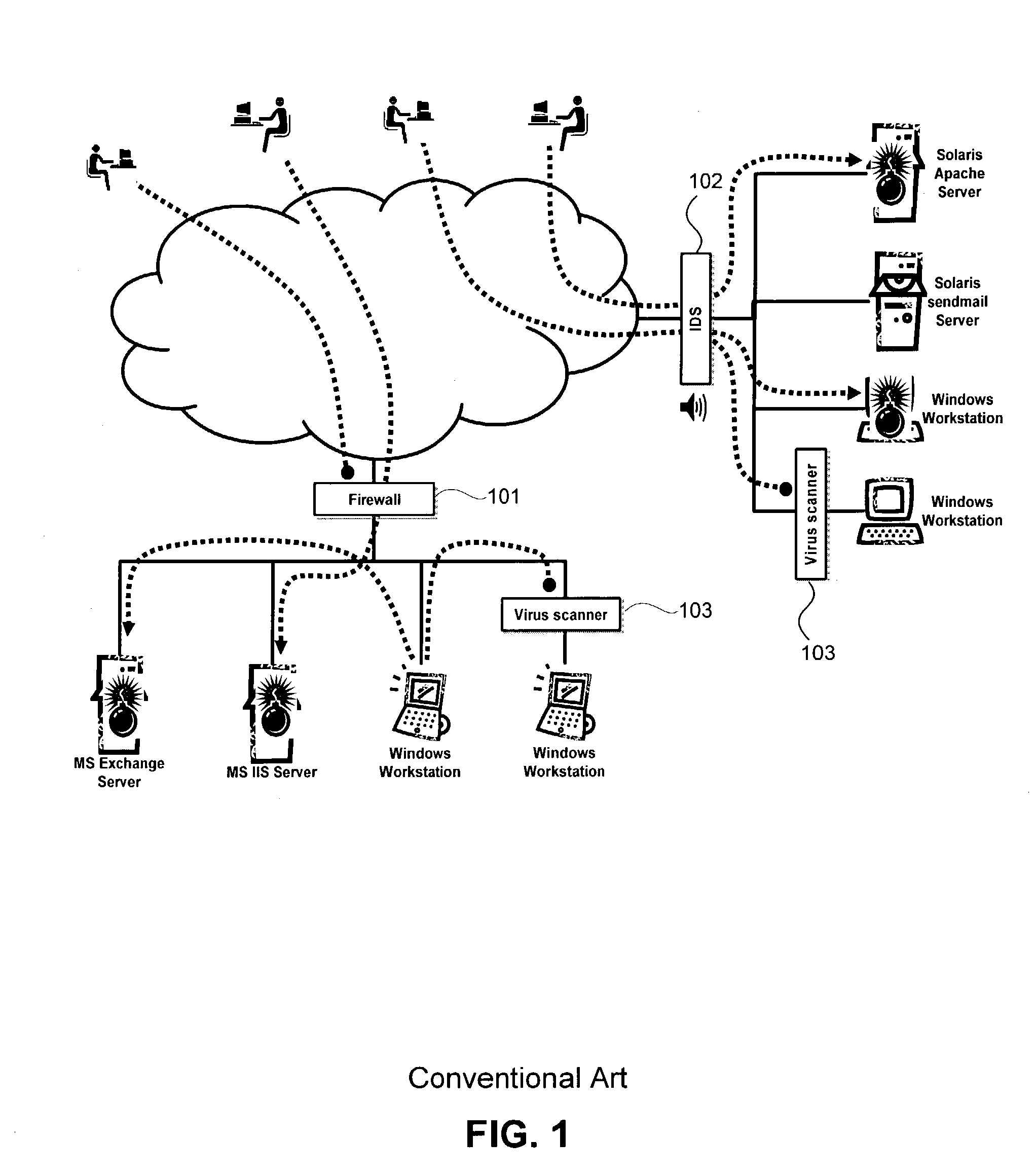

There is a growing awareness that existing security infrastructure that guards the perimeter (e.g., firewalls) or uses signatures (e.g., anti-

virus and intrusion detection) is no longer adequate protection against new and unknown attacks or hostile insiders.

Because of these mandates and the inability of

perimeter security to protect applications and servers, critical computing resources are exposed to severe and frequent damage.

When a new

attack appears (and all attacks are new and unknown at first) it slips past existing defenses (firewall, intrusion detection, and anti-virus

software) and exploits some

vulnerability in an application or

operating system (e.g.,

buffer overflow) and then causes damage to critical computing resources.

In the case of a worm or virus, if a new attack propagates quickly, as many do (e.g., NIMDA, Melissa, I Love You), it damages thousands of servers before the defenses can be updated.

In addition to automated attacks, such as viruses and worms, there is a

significant risk from malicious insiders.

Existing security products provide little defense against a malicious insider with legitimate privileges doing damage to servers.

Viruses, worms and hostile insiders cause substantial damage and loss of productivity and proprietary information and require each of the damaged servers to be repaired by reformatting, reconfiguring, recovering data or even replacing the

server.

This type of defense does not account for damage caused from inside the network.

Many studies have shown that internal attacks account for a large percentage of damage.

Market pressures force the vendors to deliver new features so rapidly that it is impossible to build

software without inherent security flaws.

The requirements for today's applications are so complex that simply delivering a working product within deadlines is difficult.

The additional effort required to create a secure design and perform

security testing is not practical.

Even if application vendors decided to make security a top priority for their products, there are significant barriers to developing secure applications.

Most software developers do not have the expertise to design and build secure software.

Additionally, secure applications are pointless without a secure foundation to host them.

Today's operating systems do not provide a secure foundation to protect applications or allow them to protect themselves.

But applying patches is not a strategic solution, because they are published only after the fact, only address known flaws, and are very cumbersome to deploy.

Even solving these problems cannot guarantee freedom from attacks.

There will always be people who misuse legitimate features of the software and cause damage to critical information.

The misuse might be accidental or malicious but the result is the same--loss of information or services and

downtime to which critical are the enterprise.

Independent reports published by

Computer Security Institute / FBI, CERT / CC, and Gartner determined that known users accessing the

corporate network from the outside cause 70% of all security breaches; 57% of the breaches are unintentional and the balance are malicious.

Further, because of the significant rise in

identity theft, it is impossible to be certain whether or not a known user is the legitimate user or an imposter exploiting the access rights of the legitimate user's identity.

This means that applications will need to be more extensible and as a consequence more complex and vulnerable.

By requiring modification to the

operating system, these solutions limit themselves to vendors who distribute their

source code, and even in those cases, since they aren't part of the basic product development process, the solutions typically

lag behind the most current versions of the operating systems.

Since every change to the

system-wide information has the potential to affect every other part, it is impractical to create very large or complex configurations.

Beyond a certain size, the author will not be able to determine whether a change has detrimental ramifications on another part of the configuration.

For this reason, the previous solutions either never reached commercial viability, or if they did, only provide simple, basic configurations and cannot be easily expanded for complex situations.

While they do a good job within their target area, they leave large portions of the system unprotected.

As a result, customers desiring overall protection of their computer systems must deploy a combination of products, each dealing with a part of the security problem.

Login to View More

Login to View More  Login to View More

Login to View More