Surgical Tray

- Summary

- Abstract

- Description

- Claims

- Application Information

AI Technical Summary

Benefits of technology

Problems solved by technology

Method used

Image

Examples

Embodiment Construction

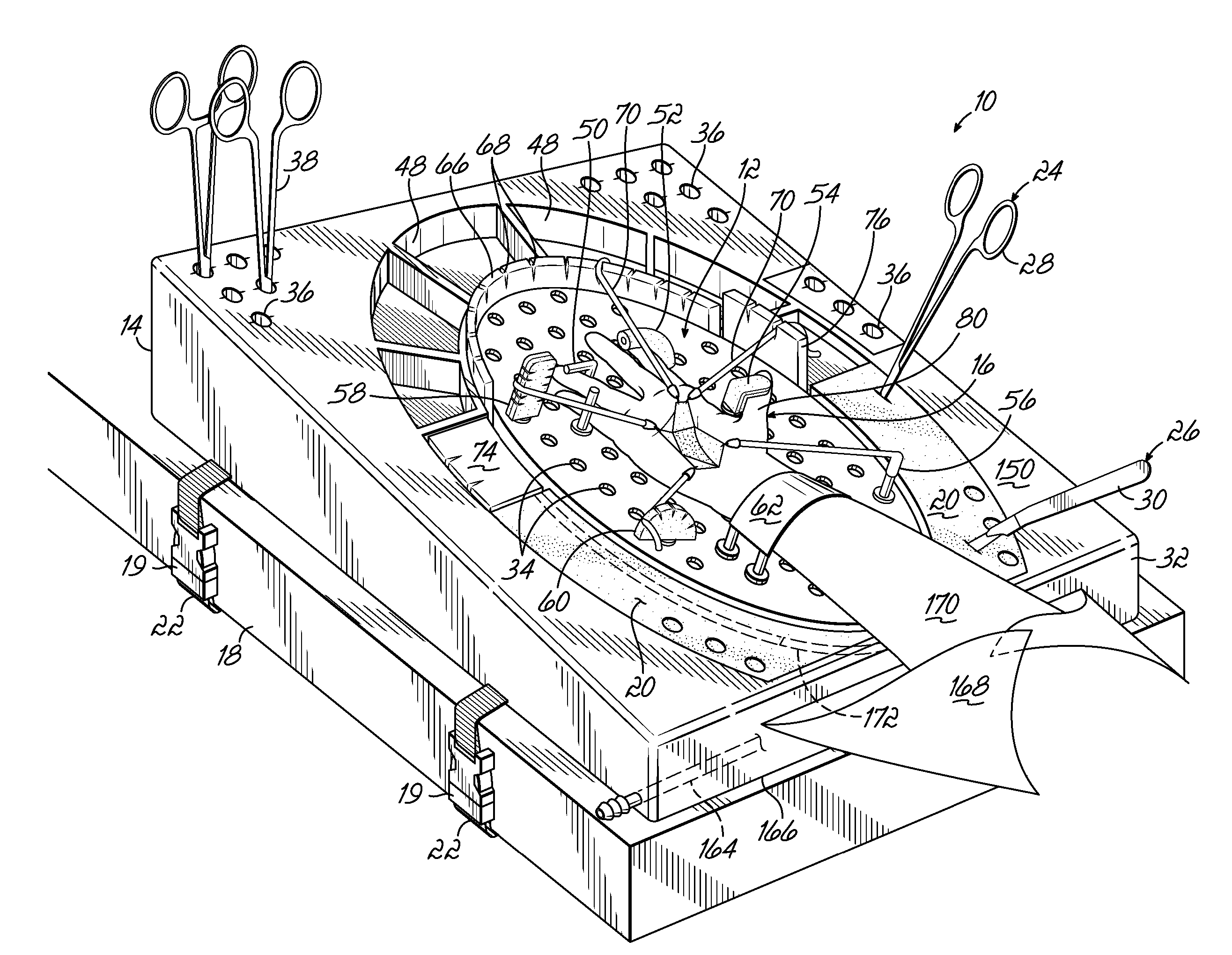

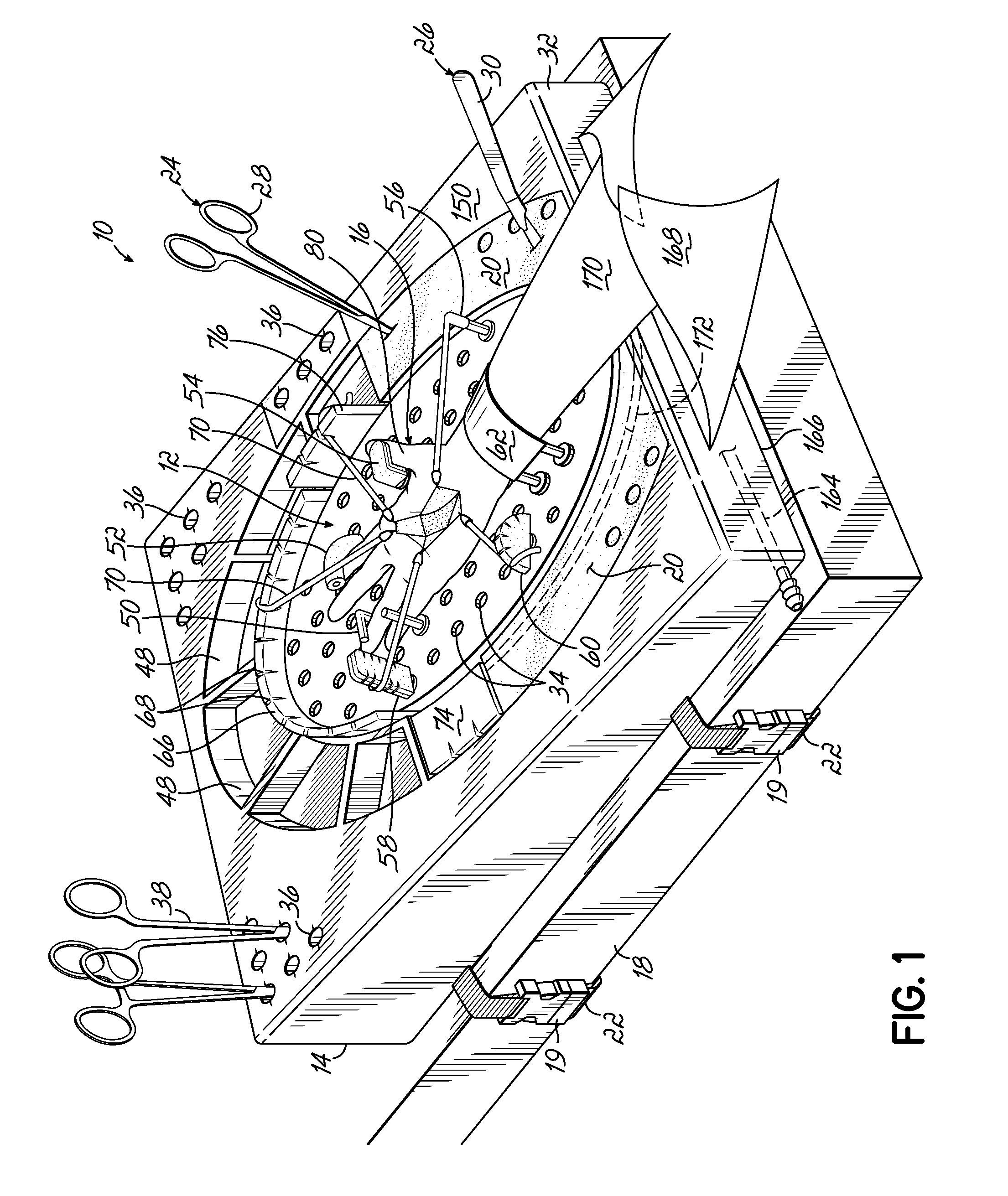

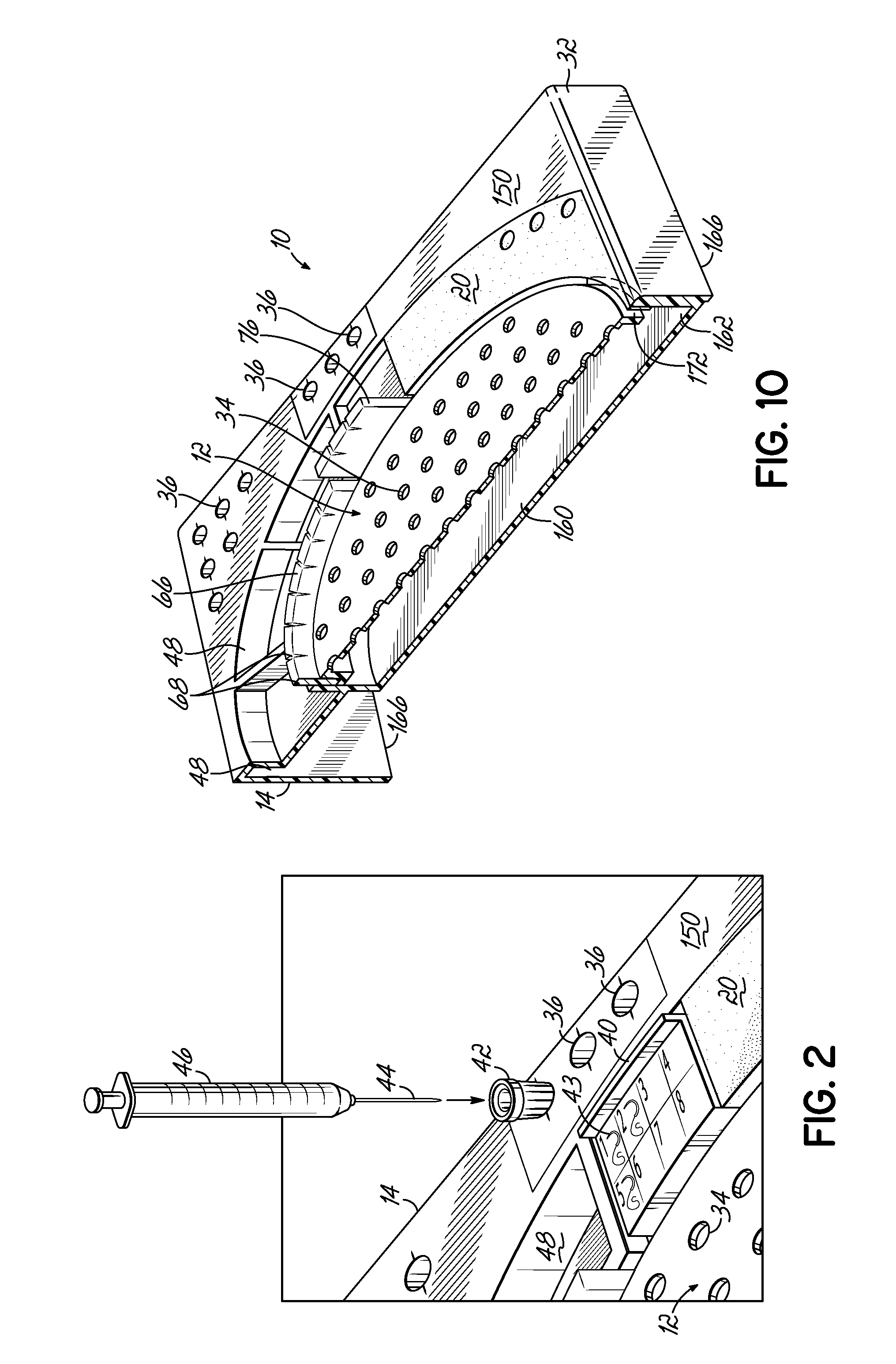

[0033] With reference to FIG. 1, a surgical tray 10 according to one embodiment of the invention is shown. The surgical tray 10 generally comprises a surgical site board 12 adapted to support a portion of a patient's body and a housing 14 configured to support the site board 12. Although FIG. 1 illustrates the site board 12 being used to support a patient's hand 16, those skilled in the art will appreciate that the tray 10 may also be used during surgical operations on other areas of the patient's body or on small animals. Additionally, although the surgical tray 10 may be particularly advantageous for emergency-room situations, the tray 10 may also be utilized for small outpatient operative areas, treatment rooms, minor surgical procedure rooms, clinics, military field hospitals, and anywhere extremity surgery can be done. In such environments the tray 10 may be secured to an operating table 18 by one or more straps 22 connected to the housing 14. The straps 22 may be secured by lo...

PUM

Login to View More

Login to View More Abstract

Description

Claims

Application Information

Login to View More

Login to View More - R&D

- Intellectual Property

- Life Sciences

- Materials

- Tech Scout

- Unparalleled Data Quality

- Higher Quality Content

- 60% Fewer Hallucinations

Browse by: Latest US Patents, China's latest patents, Technical Efficacy Thesaurus, Application Domain, Technology Topic, Popular Technical Reports.

© 2025 PatSnap. All rights reserved.Legal|Privacy policy|Modern Slavery Act Transparency Statement|Sitemap|About US| Contact US: help@patsnap.com