While the friction between the relatively rough surfaces of stacked blocks can help keep the wall together, this friction is not sufficient in many

retaining wall applications.

Unfortunately, such retaining walls are prone to

cracking due to

settling,

frost, water buildup behind the wall and earthquakes, as well as the normal use of the wall by people and animals that walk, stand, lean or sit on the wall.

A significant problem with these block designs is the expense of the extra components and increased installation costs.

These designs can also suffer from unsightly cracks that tend to form in these types of walls.

One problem with conventional

interlocking masonry wall blocks is that the thickness of the

integral projection is directly related to the amount of setback desired for each course of blocks.

Yet, thin projections are structurally weak and prone to chipping and

cracking.

While the height of the block can be increased to increase the thickness of its setback, this results in a heavier block that is more difficult to

handle.

In addition, tall blocks also do not lend themselves to

landscaping gradually sloping

terrain.

This produces an unsightly wall and results in a waste of material.

Another problem with conventional interlocking masonry wall blocks is that the

integral projection is located along the rear or

front edge of the block.

Yet, these relatively thin and weak projections are located where they are easily damaged if dropped, improperly stacked or otherwise mishandled.

In addition, rear projections are in direct contact with the wetness and acidity of the earth during use, which can cause the projection to deteriorate, weaken and fail over time.

Front projections extend upwardly and can collect water between them and the upper course of blocks, which can freeze and crack the projection.

A further problem with conventional interlocking masonry wall blocks is that the integral projections are relatively short in height to reduce the possibility of chipping and

cracking.

Although the short projections may be less likely to crack, they do not provide a sufficiently tall

abutment to easily and consistently align the block over a lower course of blocks.

During construction of a wall, workers have a tendency to leave a gap between the projection and the lower course of blocks or allow the projection to ride-up onto the upper surface of the lower block.

These misalignments are not easily detected given the thinness of the projection and its relatively small height.

This is especially so for blocks with rear projections that extend down from the lower surface of the block, because the workers are not able to easily see that the blocks are properly aligned.

Misalignments can be even more difficult to notice in construction settings where

dirt, gravel and other debris are present, and may compact against the setback projection or get on the upper or lower surfaces of the blocks.

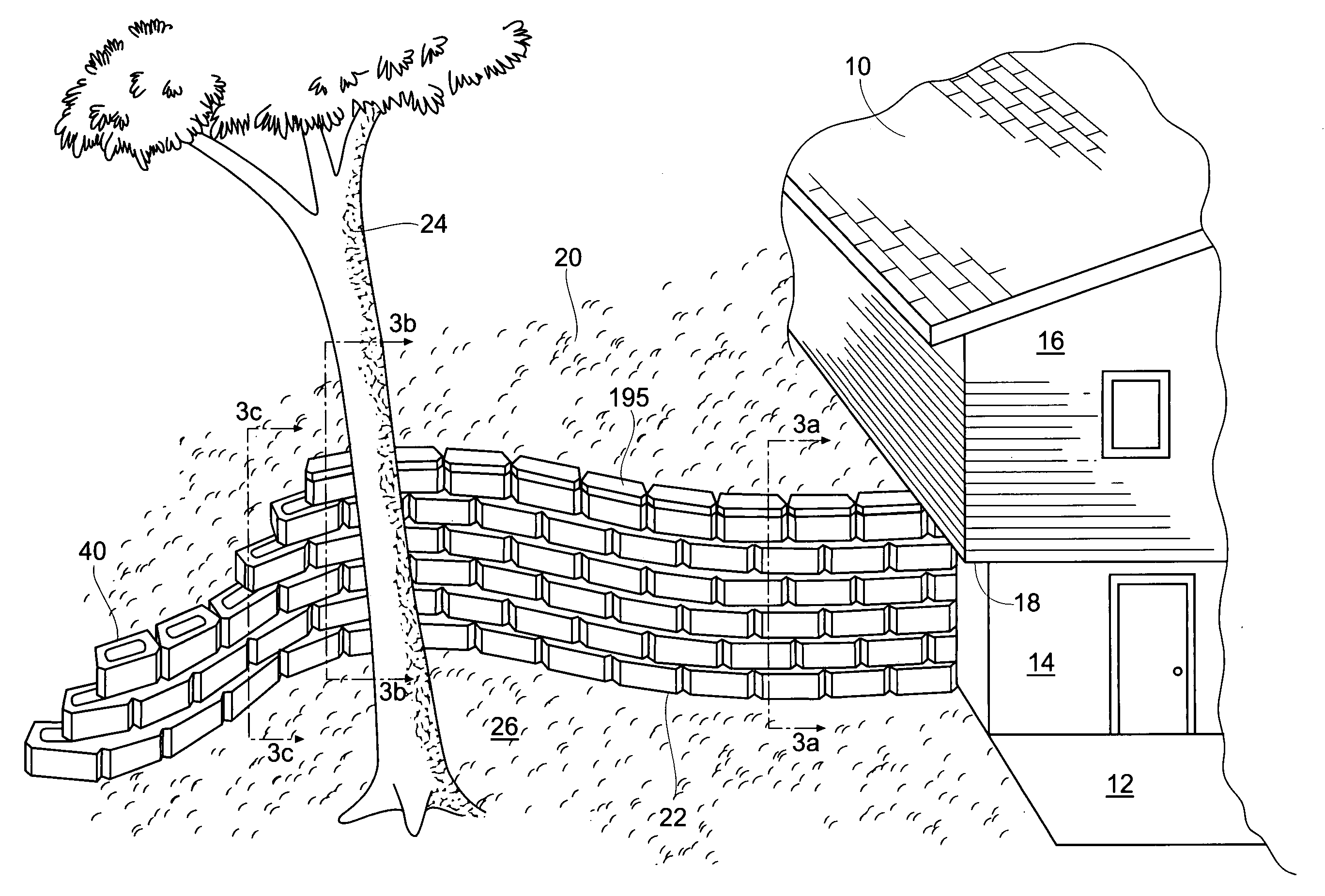

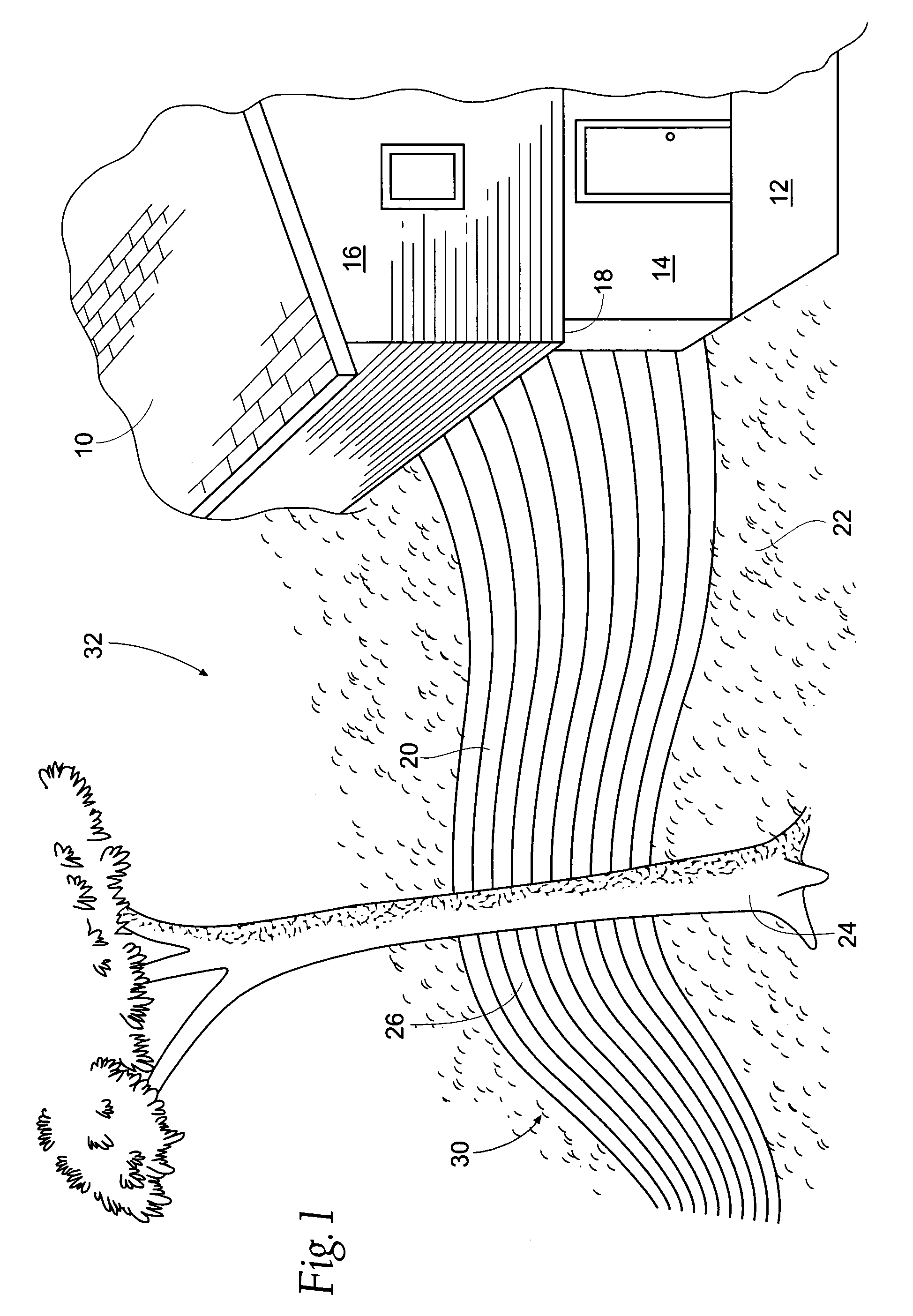

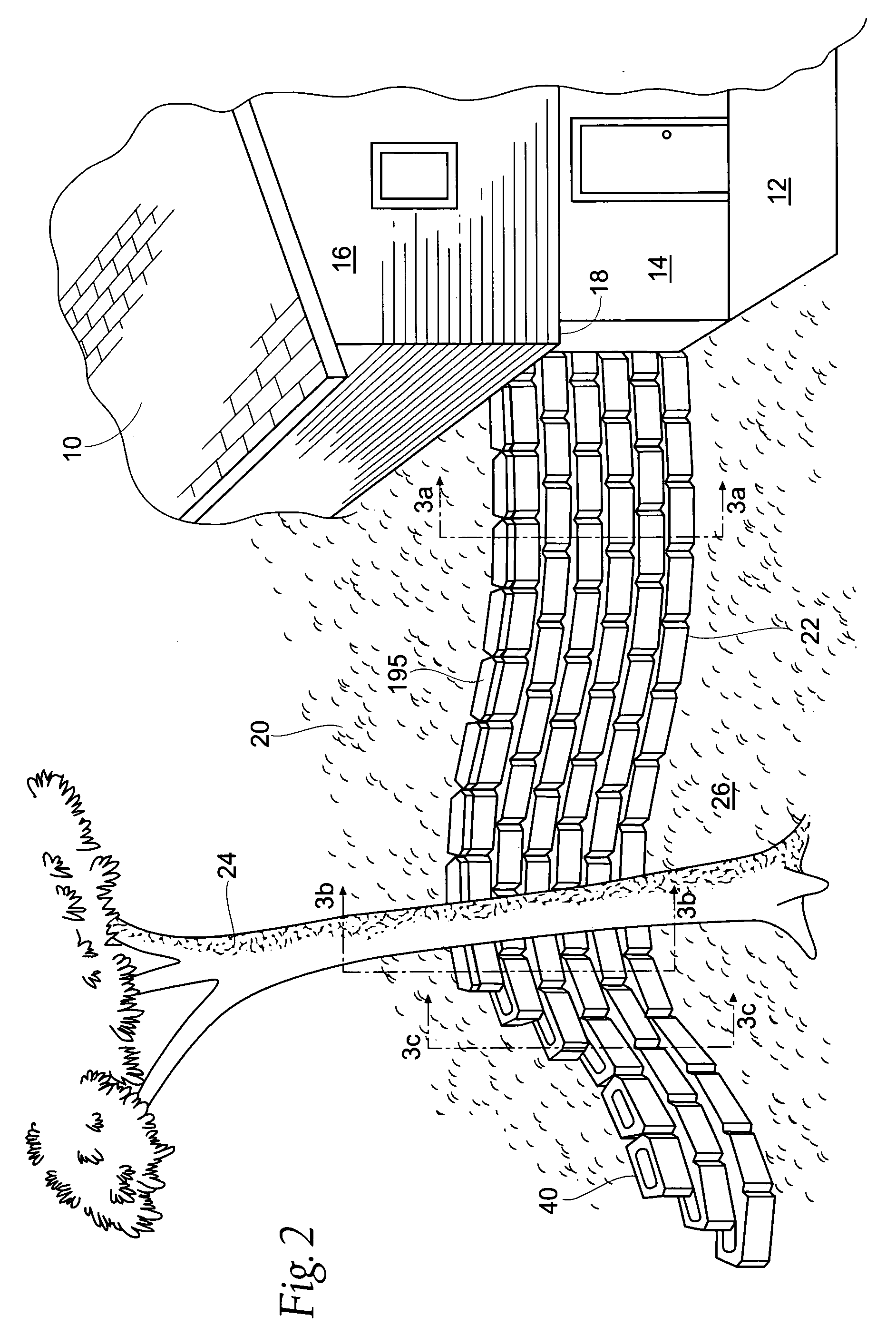

A still further problem with conventional interlocking masonry wall blocks is that they have limited ability to produce serpentine walls with straight, concave and convex portions.

If a curve is possible, the

radius of the curve is constant, so that a true serpentine wall with curves that gradually increase or decrease in

radius are not possible.

These limitations of conventional block designs prevent the wall from being integrated into the natural contours of the landscape and thus impede the aesthetic value of the wall.

A still further problem with conventional interlocking masonry wall blocks is that the integral projections do not ensure an even amount of setback for straight and curved portions of the wall.

This increasing setback and

pitch occurs even though a

retaining wall may need to be stronger and require more setback in straight portions of the wall than in curved portions.

A still further problem with conventional interlocking masonry wall blocks is that the blocks require a fixed amount of

lateral offset to the right or left of the lower blocks on which they rest.

Yet, obstructions at the location where the wall is to be built or the addition of drain pipes in the wall do not always permit each block to be offset a constant amount throughout the entire wall.

Yet, many interlocking block designs do not allow sufficient flexibility to offset the blocks as needed to accommodate various obstacles or drain pipes.

This inflexibility can complicate construction or renders the block unusable for some retaining wall applications.

A still further problem with conventional interlocking masonry wall blocks is that the

integral projection does not provide sufficient resistance to lateral side-to-side movement of the block.

However, should one block in a given course shift or move out of abutting alignment with one of its adjacent blocks, then each of the blocks in that row would be susceptible to shifting as well.

Moreover, the blocks that form an end of the wall are not restrained from

lateral movement away from its sole adjacent block and could be knocked off the wall altogether.

A still further problem with conventional interlocking masonry wall blocks is that several different block shapes must be combined to form the straight and curved sections of a serpentine wall.

The need for multiple block designs result in increased manufacturing, inventory, shipping and construction costs.

The multiple block designs also result in more complicated serpentine wall designs that are not easily integrated to the shape of a specific and unique landscape setting.

A still further problem with conventional interlocking masonry wall blocks is that they are heavy and difficult to

handle.

The

excessive weight is compounded by the fact that the block must be tall enough to provide a setback projection or

flange that is sufficiently thick to withstand cracking and chipping during transport, construction and use.

Login to View More

Login to View More  Login to View More

Login to View More