Launching device for clay targets

a launch device and clay technology, applied in the field of clay pigeon launch devices, can solve the problems of unnaturally large number of eggs laid, large range of wild pheasants, and inability to sustain the vast number of organised shoots of wild pheasants, etc., to achieve the effect of reducing the risk of injury, increasing the range, and increasing the rang

- Summary

- Abstract

- Description

- Claims

- Application Information

AI Technical Summary

Benefits of technology

Problems solved by technology

Method used

Image

Examples

Embodiment Construction

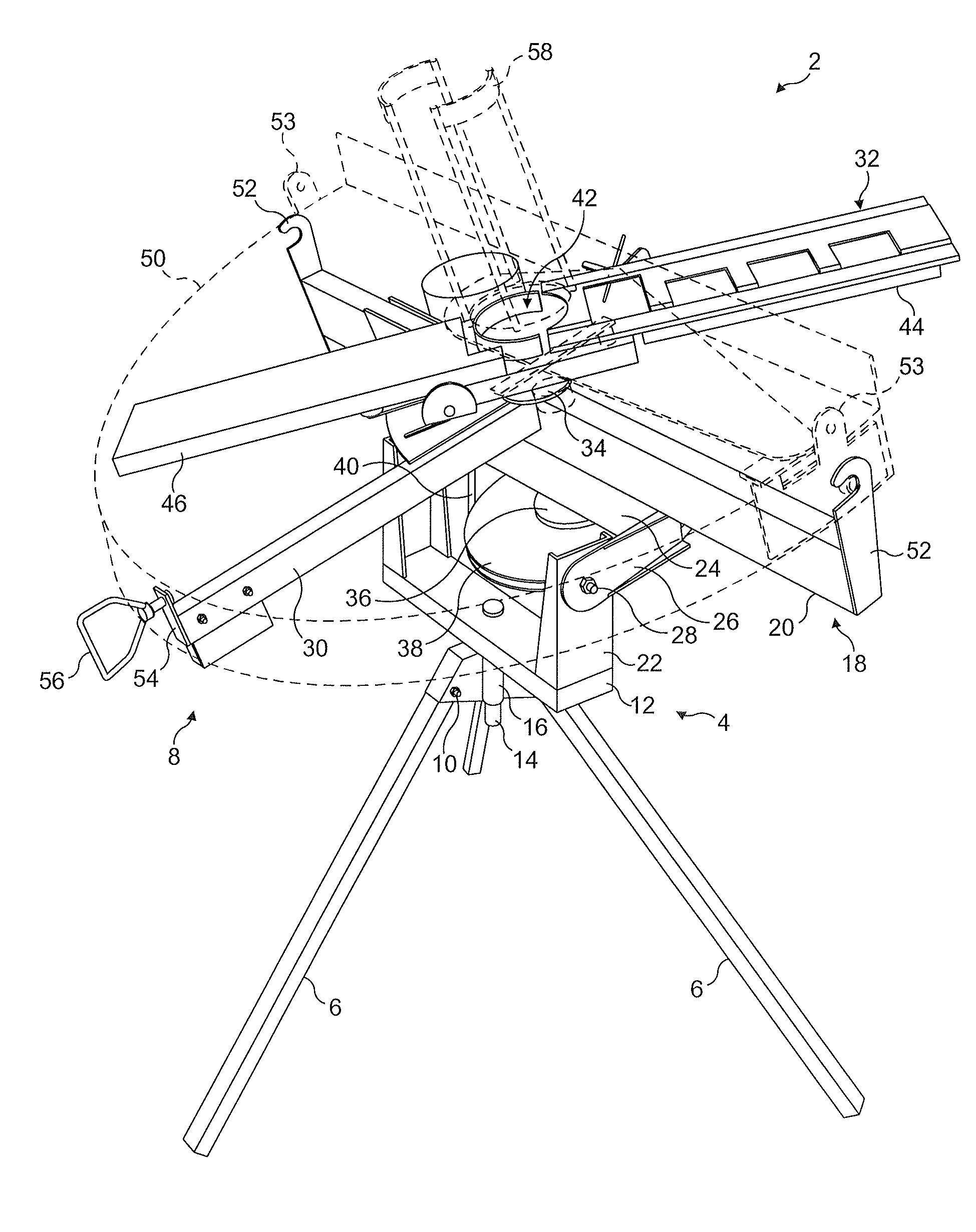

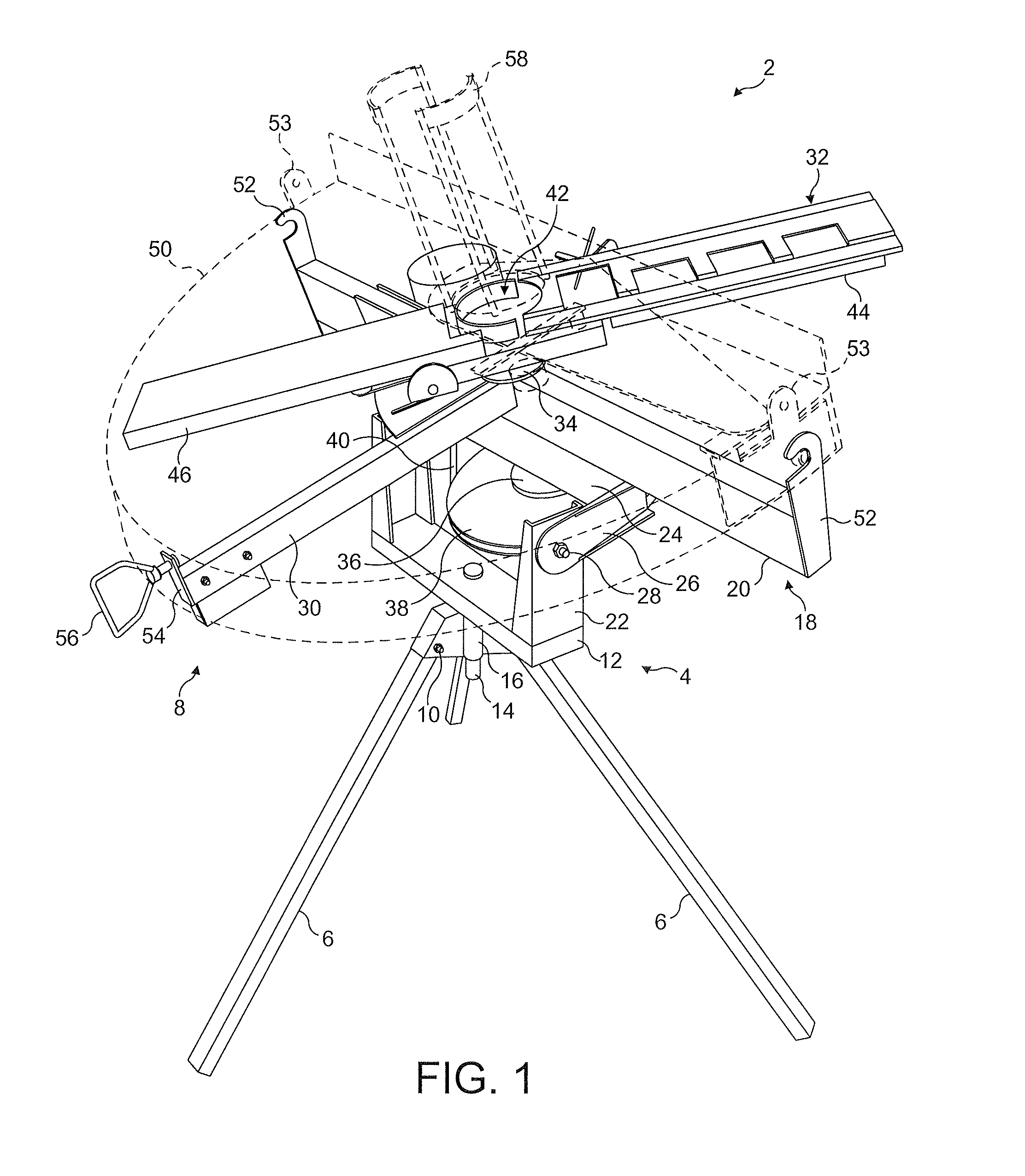

[0058]A launching device, generally indicated at 2, comprises a supporting base 4 from which depends three legs 6 supporting the launching device on the ground (not shown), and a launch assembly 8 rotatably mounted on the base 4.

[0059]The legs 6 are fixed to the base 4 by bolts 10 which allows the legs 6 to swing between a closed position, in which the legs 6 lie substantially parallel to one another, to an open position so as to define a stable triangular footprint, as shown in FIG. 1.

[0060]The rotatable mounting for the launch assembly 8 comprises a box-section steel hub 12 having a rigid, circular in cross-section, shaft 14 that depends downward from the centre of the hub 12 and extends through a tubular bearing collar 16 defined by the base 4. The hub 12 is therefore moveable angularly about the axis of the shaft 14.

[0061]The launch assembly 8 is mounted to the hub 12 via a frame-like support platform 18 comprising a laterally extending box-section steel beam 20 that is mounted ...

PUM

Login to View More

Login to View More Abstract

Description

Claims

Application Information

Login to View More

Login to View More - R&D

- Intellectual Property

- Life Sciences

- Materials

- Tech Scout

- Unparalleled Data Quality

- Higher Quality Content

- 60% Fewer Hallucinations

Browse by: Latest US Patents, China's latest patents, Technical Efficacy Thesaurus, Application Domain, Technology Topic, Popular Technical Reports.

© 2025 PatSnap. All rights reserved.Legal|Privacy policy|Modern Slavery Act Transparency Statement|Sitemap|About US| Contact US: help@patsnap.com