Trap with flush valve

a technology of flush valve and trap, which is applied in the field of trapping flying insects, can solve the problems of disease becoming major health problems, economic losses, and the cost of treatment of such mosquito-transmitted diseases, and the effect of affecting the health of people and animals

- Summary

- Abstract

- Description

- Claims

- Application Information

AI Technical Summary

Benefits of technology

Problems solved by technology

Method used

Image

Examples

Embodiment Construction

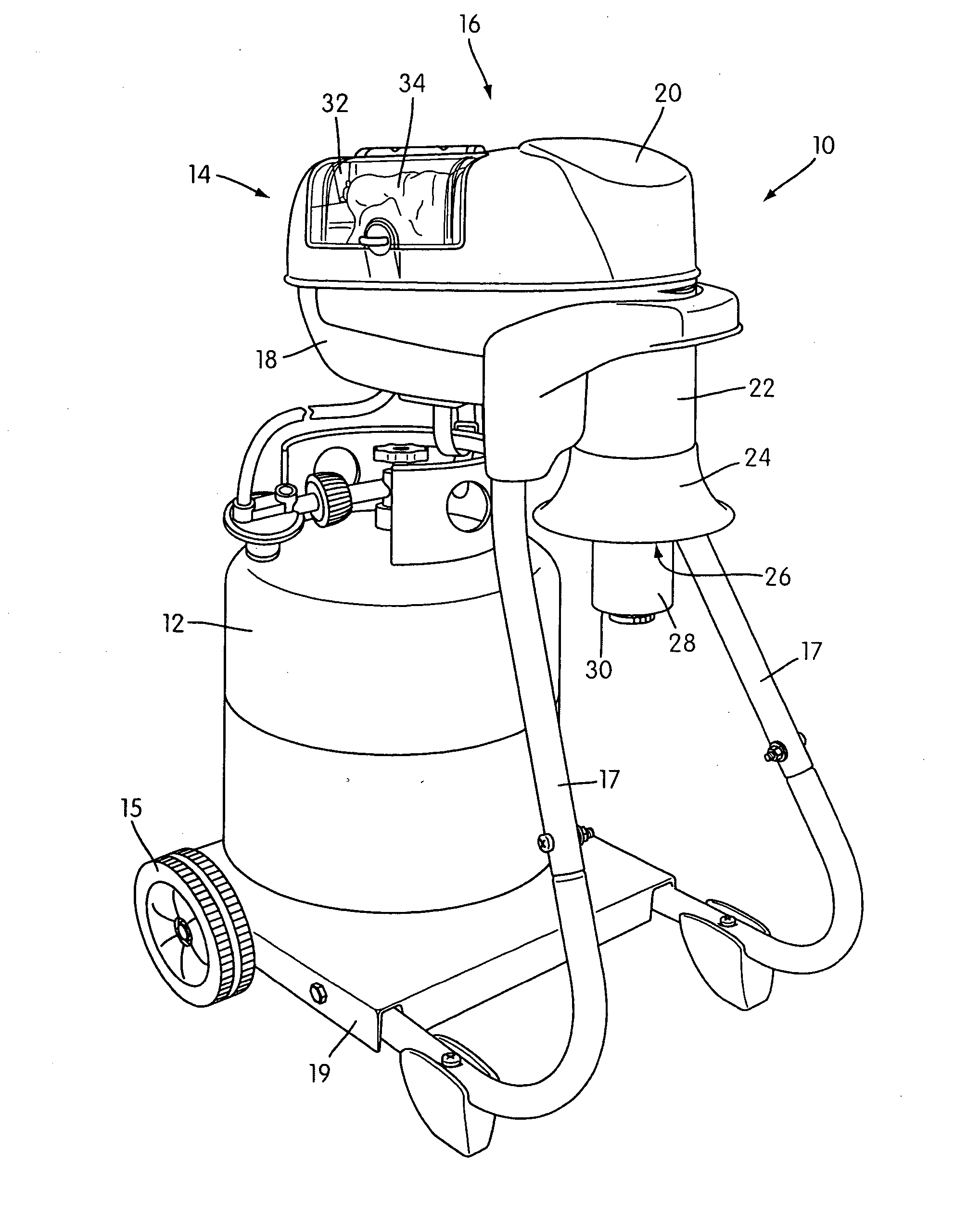

[0051] FIG. 2 is a perspective view of an exemplary flying insect trapping device, generally indicated at 10, constructed in accordance with the present invention. The device 10 is designed to be used with a supply of combustible fuel, such as a propane tank 12 of the type conventionally used by consumers for supplying fuel to a barbecue grill. Broadly speaking, the general function of the device 10 is to emit an exhaust gas with an increased carbon dioxide content to attract mosquitoes and other flesh biting insects that are attracted to carbon dioxide. Then, an inflow, draws the attracted insects into a trap chamber within the device, whereat the insects are captured and killed by poison or dehydration / starvation. Alternatively, a user engaged in the study of insects may opt to not kill the captured insects and instead may remove them from the device 10 prior to dying for purposes of live examination. Regardless of the specific insect capturing purpose the user has in mind, the ov...

PUM

Login to View More

Login to View More Abstract

Description

Claims

Application Information

Login to View More

Login to View More - R&D

- Intellectual Property

- Life Sciences

- Materials

- Tech Scout

- Unparalleled Data Quality

- Higher Quality Content

- 60% Fewer Hallucinations

Browse by: Latest US Patents, China's latest patents, Technical Efficacy Thesaurus, Application Domain, Technology Topic, Popular Technical Reports.

© 2025 PatSnap. All rights reserved.Legal|Privacy policy|Modern Slavery Act Transparency Statement|Sitemap|About US| Contact US: help@patsnap.com